Encouraging Students to Think Through Life’s Gray Areas

A summer institute alum got unexpected — and welcomed — outcomes when she created a real-life case study on shoplifting to hone her students' reading and writing skills. In this guest blog post, Shelley Sheets provides a DIY design to help you make case studies to fit your curriculum needs.

By Shelley Sheets, teacher at Ralston Middle School in Omaha, Neb.

Many things stuck with me after attending the 2016 Annenberg-Newseum Summer Teacher Institute, but the idea that stood out to me the most was reimagining classroom debate by using “case studies.” You can find 22 wonderful case studies created by NewseumED here.

The Newseum and its case studies are grounded in and founded on freedom of speech. Freedom of speech is vital now probably more than ever, but it doesn’t always directly connect to what my kids and I are studying. I teach digital literacy. I help my students hone their reading and writing skills, particularly when it comes to reading and writing in digital formats. I needed a case study that would fit into a unit on survival. So, this is the story about how I created my very own case study, and how you can, too.

Wait … What is a Case Study?

A case study gets kids discussing controversial issues, but is superior to traditional debate in several ways. Traditional debates often fall short for two reasons. First, there are only two choices. It reduces the world to black and white. The gray area is almost always where things get interesting. Second, debate (in the classic sense) centers around what students think, instead of what they would actually do in a certain situation.

A case study is based on a real-life, specific situation, or “case.” Students are given a clearly defined role to play in the situation. For instance, my case study is about shoplifting, so it involves a store owner, police officer, other shoppers, and a shoplifter. I chose to have my kids play the role of the police officer. So, a case study gives students a brief explanation of a real-life, specific situation, a role to play in that situation, and four multiple choice options for what they would do in the situation.

Case Study DIY Design

Designing my own case study was not easy, but was incredibly worthwhile. I have used it both as part of a unit about survival, and a unit about food and water justice. I take two 45-minute class periods to do the case study and follow-up activities.

First and foremost, I had to find a case. This is trickier than it may seem at first. It can’t be a super famous (or recent) case because then there’s a risk of kids already knowing what happened in real life, and thus thinking they know the “right” answer. Of course, the case also has to “live in the gray area,” meaning there is not an obvious right or wrong solution or answer.

After picking a case, the next step is to select what role your kids will take on. In my initial planning stages, I was thinking about having kids play the role of the shoplifter and of the store owner, but neither of these really made sense when trying to construct four possible, plausible reactions or outcomes. Having kids take on the role of police officer was interesting because there is so much in the news (much of it is negative, as many of my students were quick to point out) about police officers and their relationships to the communities they serve. Many kids mentioned in their reflection that they loved seeing a positive story about a police officer. Also, the police officer is the one with the power to shape the outcome of the situation. (Any decision of the store owner would eventually have to be reconciled with the police anyway.)

The next step is to come up with your multiple choice options. This is difficult because you have to come up with options that you might not personally gravitate toward, but that other people reasonably could. Also, coming up with four options that don’t overlap, and that address different shades of morality and the case itself, can be tough! It is also good to allow students to invent their own option, E. I choose to present all of this information via Google Slides, but I also print a few hard copies because some kids like to refer back to the write-up while they’re thinking through the options.

Find an article about the real-life situation to share with students after Day 1’s discussion (so, share the “true story” on Day 2). Finally, give students an opportunity to reflect after reading about what actually happened. I like to generate a list of open-ended questions, give a minimum amount of sentences that the kids must write, and then let them choose what they want to speak to.

What To Do: Day 1

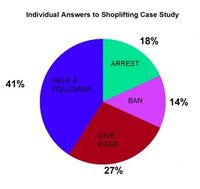

Students view the synopsis and the four multiple choice options. Have kids select which option they gravitate toward, and write reasons why. Next, they can list pros and cons of each choice on this Think Sheet. (I have also just had the kids leap straight into discussion instead of writing out their rationale and the pros and cons.) Each student is asked to turn in their personal choice written on a sticky note. Last, put students in random groups — I like a size of about four or five students — and instruct them that they must all come to an agreement on one answer. Listen in and play devil’s advocate when appropriate. Tell kids they get to find out what really happened during the next class. I had one student yell, “I need to know NOW!” (You can view a 41-second YouTube video of my students debating the case study here.)

What the Students Do: Day 2

On the second day, have kids read the article about what transpired in the real-life version of the case study. I copied and pasted the article into a Google Doc so my kids could annotate it using the Comments feature. I also used the article as a chance to have my students work on finding the main idea. After learning about what actually happened in real life and how that compares to what they decided they would do, I have my kids write a short reflection on the activity.

Unexpected Outcomes

Kids told me about their shoplifting experiences. Kids openly discussed with their classmates not knowing where their next meal was coming from. Kids wrote reflections about how at certain times of the month, their kitchen is empty. My school has 60% free and reduced-price lunch, so this was, sadly, not that surprising. It was their bravery in sharing this information that was remarkable.

Some kids become frustrated because they want more information in order to inform their decision. For instance, they often want to know if the woman stealing the eggs is homeless or if she has children to feed. But, less is more when it comes to how much information you give out in the actual case study. I usually just nudge students who are frustrated about this by saying, “Make a decision that you can live with, and that you think is fair, no matter what the backstory is.”

Even though the synopsis of the real-life scenario is very short, making a decision forces kids to read closely. For instance, many kids decide they would act differently as the police officer if the woman didn’t really need the food, versus if she (and/or her family) were going hungry. They return to the synopsis for clues, such as “she is very apologetic and doesn’t seem like she would steal if she didn’t really need the food.” This leads students to discuss whether people who are stealing “just for the fun of it” would give a meaningful apology. Also, they discuss whether they trust the information that “she doesn’t seem like she would steam if she didn’t really need the food” because seem tells us that we are just trusting some unknown narrator’s opinion.

Expected Outcomes

There will be some multiple-choice options that you don’t particularly like. And, kids will want to know what option you would pick. But this isn’t about what the teacher thinks, or would do. This is about what the kids would do.

There will be some multiple-choice options that you don’t particularly like. And, kids will want to know what option you would pick. But this isn’t about what the teacher thinks, or would do. This is about what the kids would do.

One of my favorite things about case studies is that it forces kids to examine their own ethics and morality. When kids get into their groups, they immediately begin to think about how their reaction to the case compares to that of their peers (graphs come in handy for this, too). At the end of Day 1 and/or the start of Day 2, you can even show them a graph of all of the responses in the class. Mentally comparing is natural, healthy, and, you don’t even have to assign them to do it. It’s just the way the brain works! Some memorable quotes I’ve heard are:

- “I just don’t like to see people struggle out there on the streets.”

- “Wow. You guys are really compassionate people!”

- “Why do you have to be so harsh?”

- “What if she’s homeless? What if she can’t get a job? What if she has a job, but her job doesn’t pay enough?”

- “But if she’s not arrested, other people will think stealing is OK or at least something they can get away with.”

- “People don’t always keep their promises.”

When they write a reflection, a student will often react to things he or she heard that don’t align with his or her personal moral code. Many will say the activity made them think about adjusting their own moral code. This is what really makes the activity amazing, for me. Of course I can use it to encourage my students to become better readers, writers and communicators. But more importantly, it can help them get to know themselves, get to know each other, and if we’re really lucky, maybe they will become even better people.

Shelley Sheets is a literacy coach and high ability learners coordinator at Ralston Middle School in Omaha, Neb. She has been teaching middle school ELA for 12 years and believes iced coffee should be its own food group. Sheets enjoys spending time with her daughter Adele; her husband; and their beagle and yellow lab. You can find her on Twitter: @SheetsLegitLit and via email: [email protected].

Shelley Sheets is a literacy coach and high ability learners coordinator at Ralston Middle School in Omaha, Neb. She has been teaching middle school ELA for 12 years and believes iced coffee should be its own food group. Sheets enjoys spending time with her daughter Adele; her husband; and their beagle and yellow lab. You can find her on Twitter: @SheetsLegitLit and via email: [email protected].

Want to share how you have used a lesson plan, activity or other NewseumED resource in your classroom? We welcome submissions for our website. Email them to [email protected].