Missing Piece in Media Literacy: The First Amendment

While media literacy teaches students how to analyze, evaluate and even make their own content, it often fails to instill an understanding of why these skills are so important and necessary in the first place.

At NewseumED, our First Amendment focus has long led us to tackle controversial topics, from profanity to religious discord to politics gone sour. When the 2016 presidential election started ramping up, we began hearing from educators who feared they lacked the resources to teach about a race that had become more rancorous than the norm. Unexpected twists, unfiltered gaffes and outspoken candidates had them on the hunt for new ways to bring current events into their classroom without sparking chaos. We responded with our proven approach, building concrete case studies that teased apart complex issues and supported fact-based opinions.

By the time the election results were in, teachers weren’t the only ones sensing a bigger shift in the events around us and their coverage in the news media. “Fake news” became a media phenomenon in its own way – despised but irresistible fodder for article after article, labeled everything from a dire crisis to a toothless scapegoat. News producers and aggregators feared for their reputations, while news consumers feared for their sanity. Media literacy was thrust into the spotlight, and teachers again needed tools to deal with the high-stakes, highly charged subject of junk news.

Media literacy education is not new, but the recent intensified interest in building up these essential skills has cast light on some holes in traditional approaches. While media literacy teaches students how to analyze, evaluate and even make their own content, it often fails to instill an understanding of why these skills are so important and why they’re necessary in the first place. And without laying this foundation – the reasons to beware and the reasons to care – it can be too easy for media literacy training to breed hardened cynicism. This type of disillusionment can widen societal divisions and amplify the very echo chamber effect that media literacy should combat.

At NewseumED, because of our First Amendment mission, we’ve always approached media literacy differently. We marry the analytical aspects – such as separating fact from fiction and identifying bias – with active free expression and productive social engagement. For example, consider the need to confront and counter confirmation bias. Whereas traditional media literacy might focus on how to find diverse information sources and triangulate between competing claims, we broaden the approach to also look at how confirmation bias can affect the way we express ideas and engage with pressing issues as individuals and as a society. We call this marriage of free expression and analytical skill First Amendment media literacy.

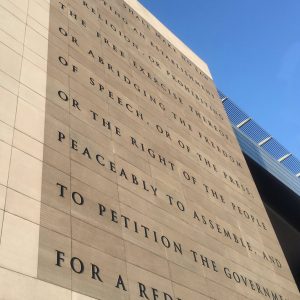

Understanding the First Amendment as a foundation for media literacy is all the more important in today’s media landscape, where the divisions between information producers, aggregators and consumers have all but melted away. In the past, the press was a distinct entity that could be held accountable for any failures to live up to its potential. Now, we are all gatekeepers, charged with deciding what we should or should not share. With no formal training, we are all expected to make daily judgments about the value of different perspectives and the purpose of various social media and self-publishing platforms. In the face of these snowballing responsibilities, we need not only technical and analytical abilities, but also a deeper understanding of how the five freedoms of the First Amendment shape the ways we create, consume, communicate and control information. Debates over free speech, religious expression and the role of the press leach into our daily lives, and the media are both the forum for and feeding into these debates. We want individuals to make active connections between the use and interpretation of our fundamental freedoms and the challenges of daily life and engaged citizenship.

The press itself is at the heart of many of these challenges. First Amendment media literacy requires exploring freedom of the press as both a vital part of a democracy, but also the root of the need for media savvy and critical thinking. We prompt students to wrestle with what it means that the First Amendment protects not only good journalism, but also flawed or half-hearted attempts at news. By digging into the decision-making processes of journalists and deconstructing their own interactions with news and information, we build an understanding of why freedom of the press must be protected, even though it will always fall short of the ideal, and why regulations or algorithms are unlikely remedies for biased, incomplete or even false information.

First Amendment media literacy takes aim at a lofty goal: to create citizens who think critically, express themselves effectively, engage openly with diverse viewpoints and effectively balance their rights and responsibilities.

The first step toward achieving this goal is breaking it down into concepts and resources that resonate with both current events and curriculum standards, making our materials classroom-ready, but also relevant to the world beyond school walls. We use real, recent examples to build our curriculum and case studies, providing needed structure for subjects that some educators might be wary of bringing into the classroom. And we pin complex concepts to more memorable formats, like our media consumer’s questions, or our tips to E.S.C.A.P.E. junk news. Our classroom activities – such as organizers that help students verify the evidence in a news story or dissect a source – can stand on their own or fold into a teacher’s existing curriculum. All of our media literacy resources are practical, flexible and in-depth enough to meet the needs of nearly any audience.

In the coming months, we’ll be rolling out new curriculum projects that will further our First Amendment media literacy offerings, digging deeper into the messy reality of the free press. We’re building classes and resources that will explore the role of propaganda in today’s age of social media and unfiltered information; help identify and counter media bias; show how to escape information bubbles to find a broader perspective; and continue our efforts to inspire and support constructive conversations about controversial issues with real-world impact.

At its heart, First Amendment media literacy is about encouraging students – and all of us – to strike a balance. As information consumers, we don’t want to be suckers, falling for every fake headline. But we also should avoid the type of hardened skepticism that makes it impossible to trust anyone or recognize facts. As contributors to the media and society as a whole, we should steer clear of being a troll who breeds hatred and misery, but also avoid being what we at NewseumED have dubbed a unicorn: someone who unconditionally likes or shares even ideas that deserve to be questioned.

The First Amendment gives us access to a full range of information and freedom to do with that information as we choose. Our hope at NewseumED is that First Amendment media literacy provides a backbone that supports informed decisions about how we wield our freedoms to shape our world.