Lesson Plan

Making a Change: Letter From Birmingham Jail

Students analyze Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail” to understand his vision for the civil rights movement.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

Sign Up

?

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

Duration

30-60 minutes

Topic(s)

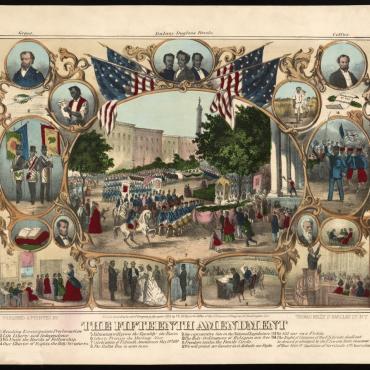

- Civil Rights

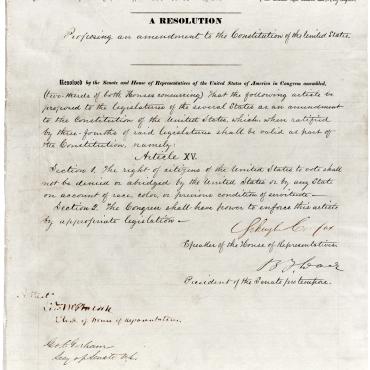

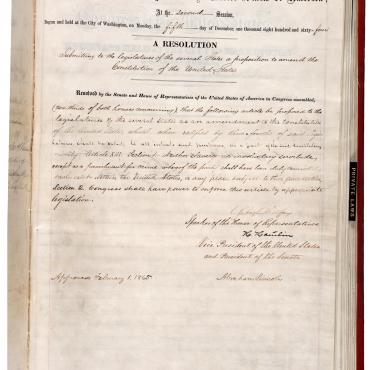

- Constitution

- Journalism

- Politics

Grade(s)

- 6-12

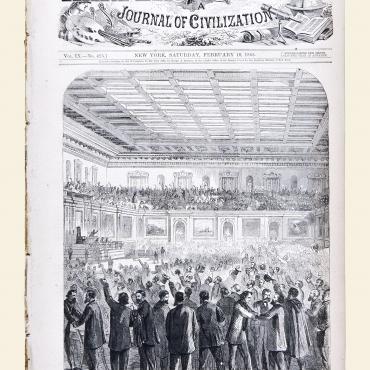

- Ask students what they know about when and why Martin Luther King Jr. wrote “Letter From Birmingham Jail.” Key points include:

- King was arrested on April 12, 1963, in Birmingham, Ala., by Bull Connor, the public safety commissioner, for parading without a permit and for defying a state order banning demonstrations.

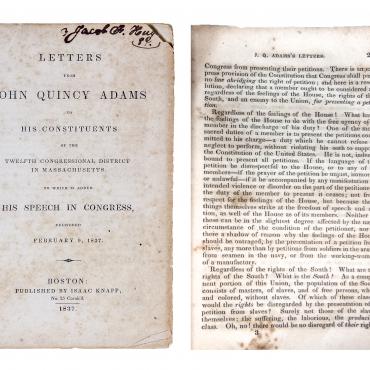

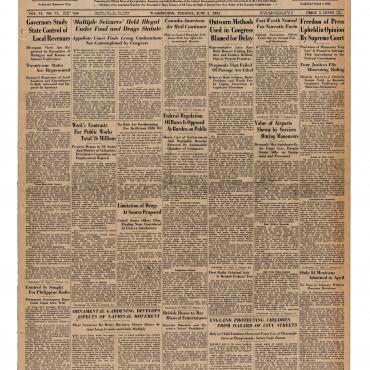

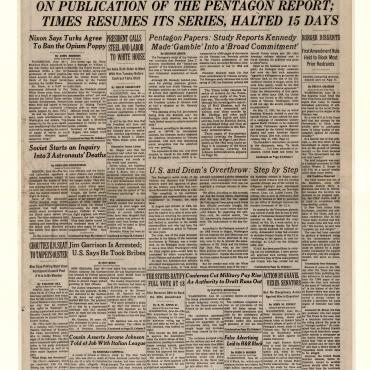

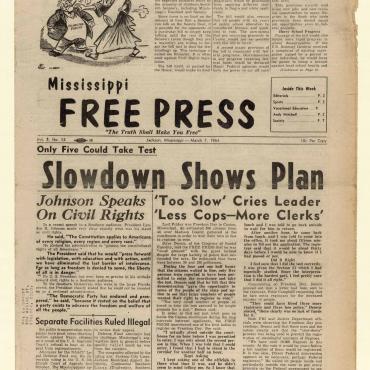

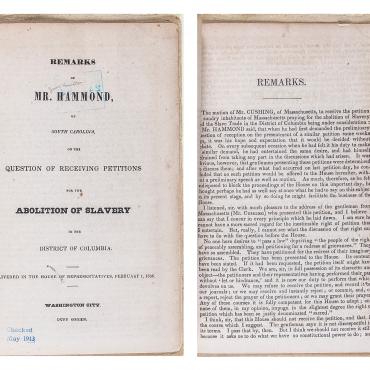

- The same day that King was arrested, a letter, signed by eight white ministers from Birmingham and titled “A Call for Unity,” was printed in The Birmingham News.

- The letter called for an end to protests and demonstrations for civil rights in Birmingham.

- King spent eight days in jail in Birmingham. On April 16, 1963, King responded to “A Call for Unity” with his own call which has come to be known as his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

- This letter was thought to be originally published in The Christian Century and was reprinted soon after in Atlantic Monthly magazine under the title “The Negro is Your Brother.”

- Distribute copies of the letters to each student.

- Give students time to read the letters.

- “Letter From Birmingham Jail” and “A Call for Unity” handouts (download), one each per student

These prompts can be used for discussion or for short essay questions for homework.

- Why were these writings — “A Call for Unity” in The Birmingham (Ala.) News and King’s response in The Christian Century and then reprinted in Atlantic Monthly — called “letters”?

- Who was the audience for the ideas expressed in each?

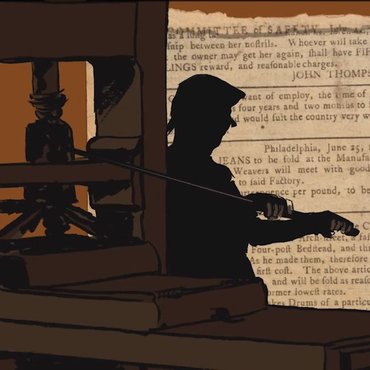

- King’s response was written in the margins of old newspapers that had to be smuggled out of his jail cell in segments by his lawyers. Why didn’t King simply write his letter and send it to The Birmingham News? Do you think it would have been published there?

- In King’s response he writes, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” What are the implications of this statement for all people in relation to social injustices? Do you believe he is right? Why or why not?

- What are the four basic steps King outlines for a nonviolent campaign? Would you add any additional steps? What are some examples of people using these approaches today?

- How does King define “just” laws and “unjust” laws? Why do you agree or disagree with his reasoning? Are there laws today that you think are unjust? If so, why are they unjust and why do people continue to obey them?

- King writes, “Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute understanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.” What does he mean by this? Do you agree with this statement? Explain.

- What definition of “extremist” does King use when he gladly accepts the label?

- If you were one of the clergymen who wrote “A Call to Unity,” how do you think you would view King’s letter? Why?

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.2

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.6

Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.9

Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

-

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.Historical Thinking.3

A. Compare and contrast differing sets of ideas. B. Consider multiple perspectives. C. Analyze cause-and-effect relationships and multiple causation, including the importance of the individual, the influence of ideas. D. Draw comparisons across eras and regions in order to define enduring issues. E. Distinguish between unsupported expressions of opinion and informed hypotheses grounded in historical evidence. F. Compare competing historical narratives. G. Challenge arguments of historical inevitability. H. Hold interpretations of history as tentative. I. Evaluate major debates among historians. J. Hypothesize the influence of the past. -

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.Historical Thinking.5

A. Identify issues and problems in the past. B. Marshal evidence of antecedent circumstances. C. Identify relevant historical antecedents. D. Evaluate alternative courses of action. E. Formulate a position or course of action on an issue. F. Evaluate the implementation of a decision. -

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.US History.Era 9

Standard 1: The economic boom and social transformation of postwar United States Standard 2: How the Cold War and conflicts in Korea and Vietnam influenced domestic and international politics Standard 3: Domestic policies after World War II Standard 4: The struggle for racial and gender equality and for the extension of civil liberties

-

National Council of Teachers of English: NCTE.1

Students read a wide range of print and non-print texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.V

A. What is citizenship? B. What are the rights of citizens? C. What are the responsibilities of citizens? D. What civic dispositions or traits of private and public character are important to the preservation and improvement of American constitutional democracy? E. How can citizens take part in civic life?