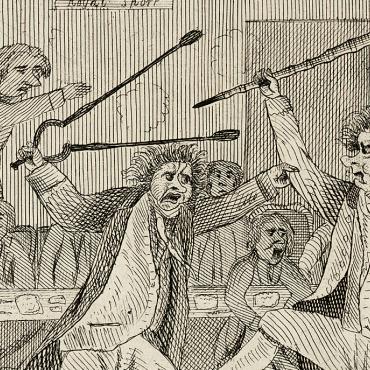

1836: Anti-Slavery Talk 'Gagged' in Congress

Should Congress, in the name of preserving peace, pass a "gag rule" to prevent abolitionists from presenting anti-slavery petitions?

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

This Critical Debate is part of a Debate Comparison:

See all Debate Comparisons- Civil Rights

- Civil War

- Politics

- 9-12

- College/University

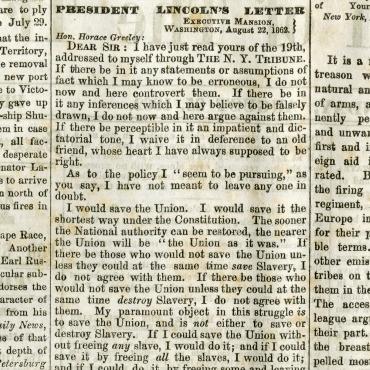

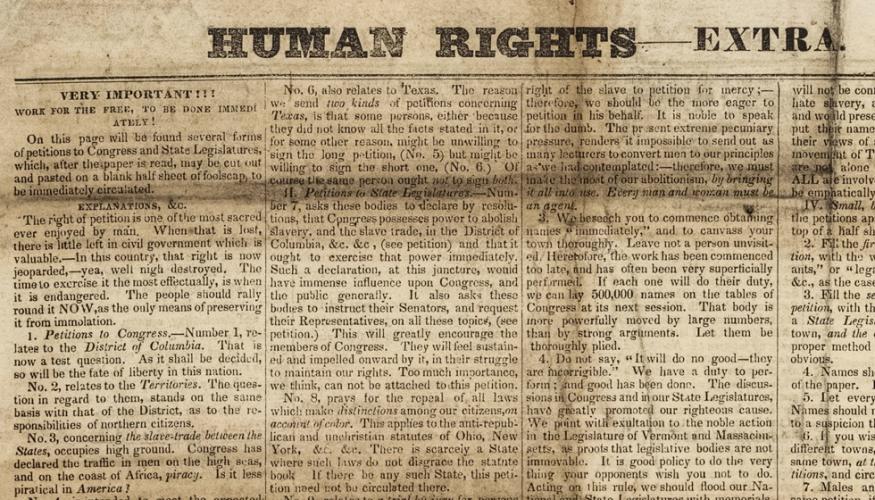

"The right of petition is one of the most sacred enjoyed by man. When that is lost, there is little left in civil government which is valuable," reads the introduction in the Human Rights, an anti-slavery publication.

- Pass out and read the Anti-Slavery Talk case study scenario. Check for comprehension and ask students to identify the First Amendment freedom(s) at issue in this case.

- Break your class into small groups and assign each group one of the people/perspectives. Hand out copies of the Organizing Evidence and Present Your Position worksheets. Give groups 30 minutes to look at the primary sources online and answer the worksheet questions.

- Have each group present their position and arguments. Keep the gallery of case study resources on NewseumED.org open so students can refer to them as they explain their reasoning.

- Historical case study handout, one per student (download)

- Organizing Evidence and Present Your Position worksheets, one of each per group (download)

- Case study primary sources (below)

- NewseumED Gag Rule Related Resources Pinterest Board (optional)

Does freedom to petition include the right to raise controversial topics that may lead to violence?

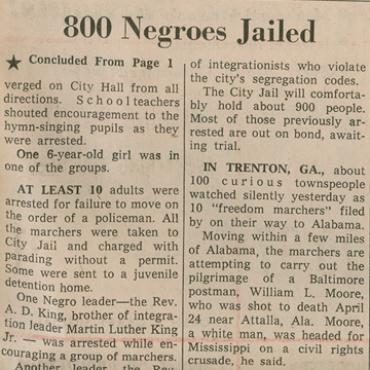

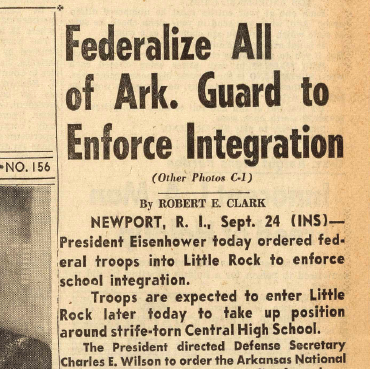

In the 1830s, Nat Turner’s Rebellion – which left nearly 60 white people dead in Virginia – has created widespread fear of further slave insurrections. The future of slavery is hotly debated in homes and in Congress. Representatives of Southern states defend slavery as a necessary and legal social and economic system, while anti-slavery representatives argue that it’s time for the promise of liberty in the Declaration of Independence to be extended to all.

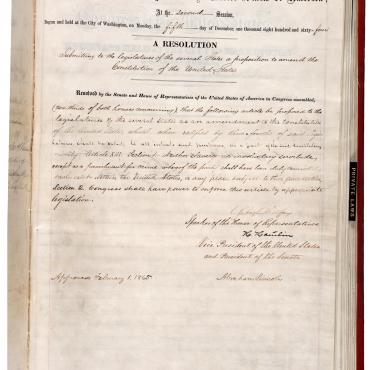

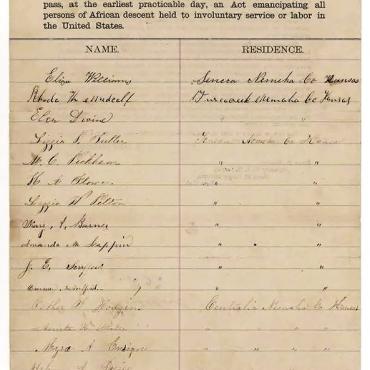

By 1836, Congress has been flooded with hundreds of petitions containing thousands of signatures for and against slavery. In the House, a group of abolitionists call for outlawing slavery in the District of Columbia. Southern representatives respond with a proposal to refuse to receive any petitions dealing with the subject of slavery. That proposal is too divisive and voted down, but then Reps. Martin Van Buren and Henry Pinckney offer a new version:

“Resolved, that all petitions, memorials, and papers touching the abolition of slavery or the buying, selling, or transferring of slaves in any state, district or territory of the United States be laid upon the table without being debated, printed, read or referred and that no further action whatever shall be had thereon.”

Some see receiving but not discussing petitions as a reasonable compromise; others declare it an outrageous constitutional violation.

Take the role of a historical figure below and find evidence to argue your case.

-

?John Quincy Adams's eight-year fight to repeal the "gag rule," though a successful campaign, further heightened North-South divisions over the issue of slavery.Courtesy White House Historical Association/White House Collection

?John Quincy Adams's eight-year fight to repeal the "gag rule," though a successful campaign, further heightened North-South divisions over the issue of slavery.Courtesy White House Historical Association/White House CollectionRep. John Quincy Adams, Massachusetts

This is not simply a debate about slavery, but about the Constitution. The Constitution grants freedom to petition the government, and Congress should receive and consider all petitions, including those from slaves and about slavery.

"Well, sir, you begin with suppressing the right of petition; you must next suppress the right of speech in this House; for you must offer a resolution that every member who dares to express a sentiment of this kind [against slavery] shall be expelled, or that the speeches shall not go forth to the public – shall not be circulated. What will be the consequence then? You suppress the right of petition; you suppress the freedom of speech; the freedom of the press, and the freedom of religion; for, in the minds of many worthy, honest, and honorable men … this is a religious question, in which they act under what they believe to be a sense of duty to their God."

-

?John Calhoun argued that slavery was a "justifiable good." Though he died before the Civil War, Calhoun laid a foundation for the secession movement.Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Arts Association

?John Calhoun argued that slavery was a "justifiable good." Though he died before the Civil War, Calhoun laid a foundation for the secession movement.Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Arts AssociationSen. John C. Calhoun, South Carolina, one of the first to propose that Congress block anti-slavery petitions

The issue of slavery is threating to tear this nation apart. Petitions against slavery will only serve to cause chaos in Congress and drive us toward war.

"Unless [anti-slavery petitions] be speedily stopped, it will spread and work upwards til it brings the two great sections of the Union into deadly conflict."

-

?John Patton practiced law in Virginia before being elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1830, where he served for eight years.Courtesy Bob Patton

?John Patton practiced law in Virginia before being elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1830, where he served for eight years.Courtesy Bob PattonRep. John M. Patton, Virginia, sponsored a resolution that declared slaves do not have the right to petition

Anti-slavery petitions, and especially those coming directly from slaves, will only lead to problems. Congress has no obligation to consider petitions from slaves, and those who urge Congress to do so do not have the best interests of the nation at heart.

"Resolved, That the right of petition does not belong to the slaves of this Union, and that no petition from them can be presented to this House, without derogating from the rights of slaveholding states, and endangering the integrity of the Union. Resolved, That any member who shall hereafter present any such petition to the House, ought to be considered … an enemy of the Union."

-

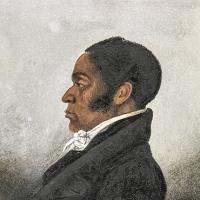

?James Forten was born a free man in Philadelphia and ran a successful sailmaking business. He was a leader of the early abolitionist movement.Courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania

?James Forten was born a free man in Philadelphia and ran a successful sailmaking business. He was a leader of the early abolitionist movement.Courtesy Historical Society of PennsylvaniaJames Forten, African-American leader and abolitionist

As citizens of the United States, we should be able to turn to Congress to ask for help with the problems we face. We don’t ask for anything beyond what the Constitution allows.

"Are we not sustained by the same power, supported by the same food, hurt by the same wounds, pleased with the same delights, and propagated by the same means. And should we not then enjoy the same liberty, and be protected by the same laws?"

- Is refusing to read a petition the same as not allowing people to submit a petition? Why does this matter?

- Should a history of violence affect reception of a petition? What about a threat of future violence?

- Is the right of petition meaningful if the government doesn’t have to respond?

- Is there a difference between informally ignoring certain types of petitions and creating an official rule to treat them differently?

-

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.Historical Thinking.4

A. Formulate historical questions. B. Obtain historical data from a variety of sources. C. Interrogate historical data. D. Identify the gaps in the available records, marshal contextual knowledge and perspectives of the time and place. E. Employ quantitative analysis. F. Support interpretations with historical evidence.

-

National Council of Teachers of English: NCTE.1

Students read a wide range of print and non-print texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.II

A. What is the American idea of constitutional government? B. What are the distinctive characteristics of American society? C. What is American political culture? D. What values and principles are basic to American constitutional democracy?