The Power of the Crowd

Explore why supporters — and opponents — of candidates attend political rallies, even in an age of digital communications and virtual reality.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Elections

- Politics

- 6-12

- College/University

A photograph in Time magazine shows a fraction of the more than 10,000 supporters that filled Bernie Sanders's rally at the Meadow Amphitheater in Irvine, Calif., on May 22, 2016.

- Ask students to brainstorm all the ways the public is involved in the election process. Can individuals make a difference?

- This case study is one of three in the Public Participation section of the Decoding Elections EDCollection that looks at the use of social media, campaign events and efforts to change a political process that some consider unfair. Explain that the case study they will be looking at will raise questions about efficacy of public engagement in the election process.

- Read the Explore the Debate question aloud and/or write it on the board. Read them the overview that sets the scene for group work. Tell them they will use historical and contemporary examples to reach a consensus in small groups on an answer to the debate question.

- Pass out copies of the case study and the Organizing Evidence worksheet. Have the groups read each of the four Election Essentials and use the Questions to Consider to help guide the discussion. They should complete sections 1 and 2 on the worksheet.

- Have the students look at the Pages From History artifacts for the case study on NewseumED.org and complete section 3 on the worksheet. Give the groups 15 minutes to collect and organize information to formulate evidence-supported arguments for their answer to the debate question. (If time is an issue, skip the artifacts or assign as homework.)

- Ask the groups to share their conclusions and reasoning. You may want to use the Questions to Consider again to push and expand the debate.

- Copies of the case study handout, one per student (download)

- Organizing Evidence worksheet, one per group (download)

- Access to NewseumED.org case study artifacts

- NewseumED Pinterest board of related resources (optional)

In an age of digital communications and virtual reality, why do citizens still turn out – often in droves – to see political candidates?

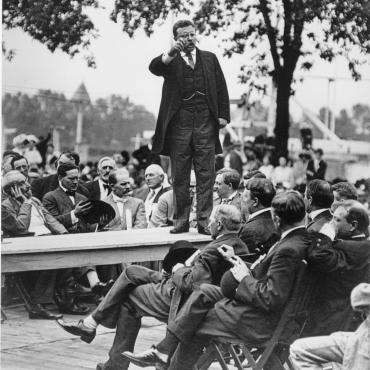

Political rallies can be great theater. With staffers building buzz days beforehand, pundits analyzing streams of tweets, and candidates roaring catchy slogans, attendees can enjoy the feverish energy of a sports match. In the 2016 presidential race, candidates bragged about the size of their crowds and complained about media neglect. Candidates and crowds feed each other — each relishing their role in the political process.

1. Size Matters

In the young republic, the U.S. public did not want presidential candidates to actively campaign; it would be undignified. However, it was perfectly acceptable for party members to organize events for their candidate. By the late 1800s, enormous parades drew thousands to city streets. One historian observed that these “demonstrations” made it look like “the whole population was with” Democrat Grover Cleveland or Republican Benjamin Harrison. Supporters knew that they could convince voters to join them — or opponents to give up — if it looked like their candidate had strong support.

2. Getting a Microphone

Rallies offer voters a way to show support for a candidate, but also opportunities to get their priorities heard. When Republican nominee William McKinley campaigned from his front porch in Canton, Ohio, during the 1896 election, he invited select groups to join him. Delegations representing “sound money” political clubs, industrial workers and more got to deliver speeches on his lawn. Although McKinley screened the remarks in advance to ensure they supported his ideas, these groups got special access to their candidate and media coverage for their causes.

3. A Place for Protest

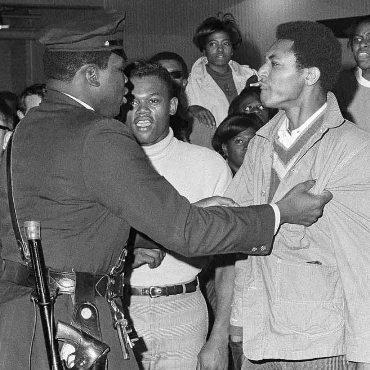

Even in tightly controlled events, candidate opponents can find ways to seize the mic. Protesters have the power to disrupt rallies using signs, gestures and chants, undermining a candidate’s promise of effective leadership. During the 1968 election, civil rights activists targeted third-party candidate George Wallace, an outspoken segregationist. They booed and mockingly chanted the Nazi slogan “sieg heil” as he spoke at events in New York and Detroit. Wallace reacted by calling them “anarchists” and urging his supporters to “manhandle” them. News coverage of the confrontations hurt Wallace’s campaign and fed the public perception that he was “dangerous.”

4. Making the History Books

Candidates with enough support can shape election outcomes, even if they don’t win a race. In spring 2016, when Hillary Clinton appeared to have a lock on the Democratic Party’s nomination, fellow candidate Bernie Sanders started drawing huge crowds to his rallies. His official slogan, “A Political Revolution Is Coming,” and his unofficial slogan, “Feel the Bern,” reflected feelings by his supporters that they could radically change U.S. politics and shape history — if they could just amass enough primary victories. Like William Jennings Bryan, another populist candidate 120 years earlier, Sanders lost to the establishment candidate, but his visibility and popularity pressured the Democratic Party to adopt some of his policy demands.

- What are the main purposes of a rally?

- What factors do you think news outlets consider when deciding which rallies to cover?

- What role should the media play? Should they report on every rally or only rallies where something unusual happens?

- How is social media coverage similar to and different from mainstream news media coverage of a rally? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each for gauging a rally’s impact?

- Why is it possible for some candidates to draw huge crowds but fall short in primary or general elections?

Find images of two campaign rallies held by two different candidates running in the same presidential, state or local election. Describe each of the four images in detail. What does it show? The candidate? Supporters? Protesters? What can you tell about the event from this image? What impact do you think this event had on the candidate’s campaign? Then, create lists of similarities and differences between the rallies based on your observations.

What’s your political personality type?

What’s your political personality type?

Make Your Voice Matter

Under 18 and can't vote?

Check out other ways to get involved.

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

-

NCSS C3 Framework: D4.1.6-8 and D4.1.9-12

6 - 8: Construct arguments using claims and evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging the strengths and limitations of the arguments. 9 - 12: Construct arguments using precise and knowledgeable claims, with evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging counterclaims and evidentiary weaknesses.

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.II

A. What is the American idea of constitutional government? B. What are the distinctive characteristics of American society? C. What is American political culture? D. What values and principles are basic to American constitutional democracy?

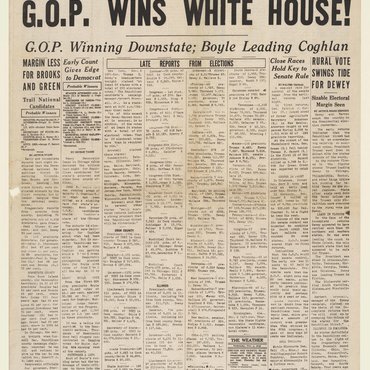

![McKinley's well organized campaign and party support helped him claim the nomination. The crown lists the states: "Mass., Texas, Maryland, Illinois, Ohio, New York, Pennsylvania, Cal. [and] Va."](/sites/default/files/styles/370x370/public/legacy/2016/08/G54627-28919u-dr_1.jpg?itok=6sp50WRq)