Religious Tests For Public Office: Seven States Ban Atheists from Holding Public Office

This text set invites students to consider the Constitutional protections for atheists in the US and the potential impact of the growing number of religiously unaffiliated Americans.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Religious Liberty

Videos are provided by NewseumED as an educational resource and are not intended for download, republication, or sharing without permissions.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Seven states have unenforced bans on atheists holding public office.

-

The Supreme Court ruled in 1961 that the religious freedom clauses of the First Amendment protect the rights of people of all faiths and none to be eligible for public appointments.

-

That is critical because a growing number of Americans, especially younger ones, identify as religious “nones.”

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

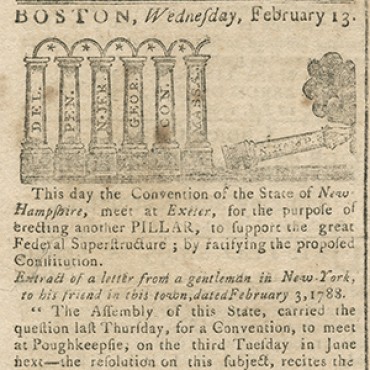

The United States Constitution maintains that "no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust." Laws called religious “Test Acts” were common at the time the constitution was written, both in Anglican-run England and the American colonies. They effectively barred Catholics and non-Anglican Protestants from holding civil offices. However, many of the men who framed the Constitution believed that such tests were useless and potentially damaging to a robust democracy. As James Iredell argued at the North Carolina Constitutional Ratifying Committee in 1788, those without a conscience would easily lie to qualify themselves for office while “the best men would be kept out of our counsels.”

Even after religious tests were banned by the U.S. Constitution, similar tests were included in state constitutions. Today, seven states — Arkansas, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas — still prohibit atheists from holding public office. Pennsylvania’s constitution ensures believers’ right to hold office, but it does not mention nonbelievers.

These statutes went largely unchallenged until 1961 when Roy Torcaso’s case was heard before the Supreme Court. Torcaso refused his appointment as a notary public by the governor of Maryland because he would not swear an oath affirming the existence of God as required by the state constitution. Torcaso was an atheist and argued that the oath violated his First Amendment right to religious freedom. The Supreme Court agreed, ruling that a person could not be denied office for being an unbeliever because it "unconstitutionally invades his freedom of belief and religion guaranteed by the First Amendment.”

Since then, a rapidly growing number of Americans have ceased to affiliate with a religious tradition. Often called religious “nones,” these atheists, agnostics and unaffiliated make up a growing percentage of younger Americans in particular. While only 17% of Baby Boomers identify as religious “nones”, 36% of millennials identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” with 7% of millennials identifying specifically as atheist. Among Gen-Z, 35% identify as religiously unaffiliated with 13% identifying specifically as atheist. This means while the total proportion of religious “nones” among millennials and Gen-Z are similar, there are about twice as many Gen-Z atheists.

Does that mean that a significant portion of young Americans cannot run for office in those seven states? No. Atheism is not a religion, but it is still protected by the same constitutional provisions that guard the rights of Christians, Muslims, Buddhists and any other religious tradition. The First Amendment’s religious freedom clauses protect our consciences, whether they are guided by a religious or nonreligious worldview.

While these bans technically remain on the books, the good news is that anyone who wants to challenge them would likely win. For example, in 1992 and 2009, similar cases in South Carolina and North Carolina respectively were decided in the atheists’ favor. The First Amendment ensures that whatever your deepest beliefs may be, you have every right to participate in the American democratic process whether that’s through voting, lobbying or running for elected office.

U.S. Constitution, Art. VI, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript

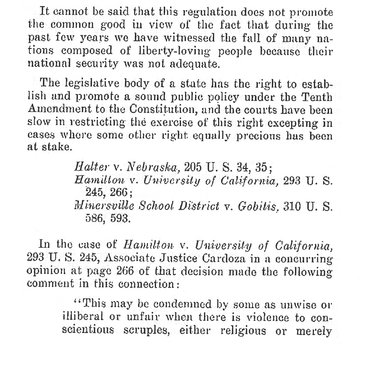

Article VI of the U.S. Constitution contains the original prohibition of religious test requirements. This article states “the senators and representatives...and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.”

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 (1961) https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/367/488/#tab-opinion-1943397

In this landmark case, the Supreme Court found that requiring an oath to affirm belief in the existence of God in order to hold public office violates the First and the Fourteenth Amendments. The case centered around Roy Torcaso, an appointed notary public whose commission was denied because he refused to affirm his belief in the “existence of God.” In the majority opinion, Justice Hugo Black declared the use of this religious test unconstitutional, arguing that the “Maryland religious test for public office unconstitutionally invades the appellant's freedom of belief and religion, and therefore cannot be enforced against him.”

“An Originalist Analysis of the No Religious Test Clause,” Harvard Law Review, April 1, 2007 https://harvardlawreview.org/2007/04/an-originalist-analysis-of-the-no-religious-test-clause/

This unsigned note in the Harvard Law Review’s Constitutional Theory section thoroughly covers how the framers of the Constitution understood the no religious test clause of Article VI. Section 1, A and B (pgs. 1650-1659) are particularly useful for understanding the history of religious tests in Europe and America as well as an analysis of the clause’s relation to the oath clause that precedes it in the Constitution. Additionally, the note details the reasoning of those framers who argued for and against the clause.

Gregory R. Smith, “About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Are Now Religiously Unaffiliated,” Pew Research Center, December 14th, 2021, https://www.pewforum.org/2021/12/14/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-are-now-religiously-unaffiliated/.

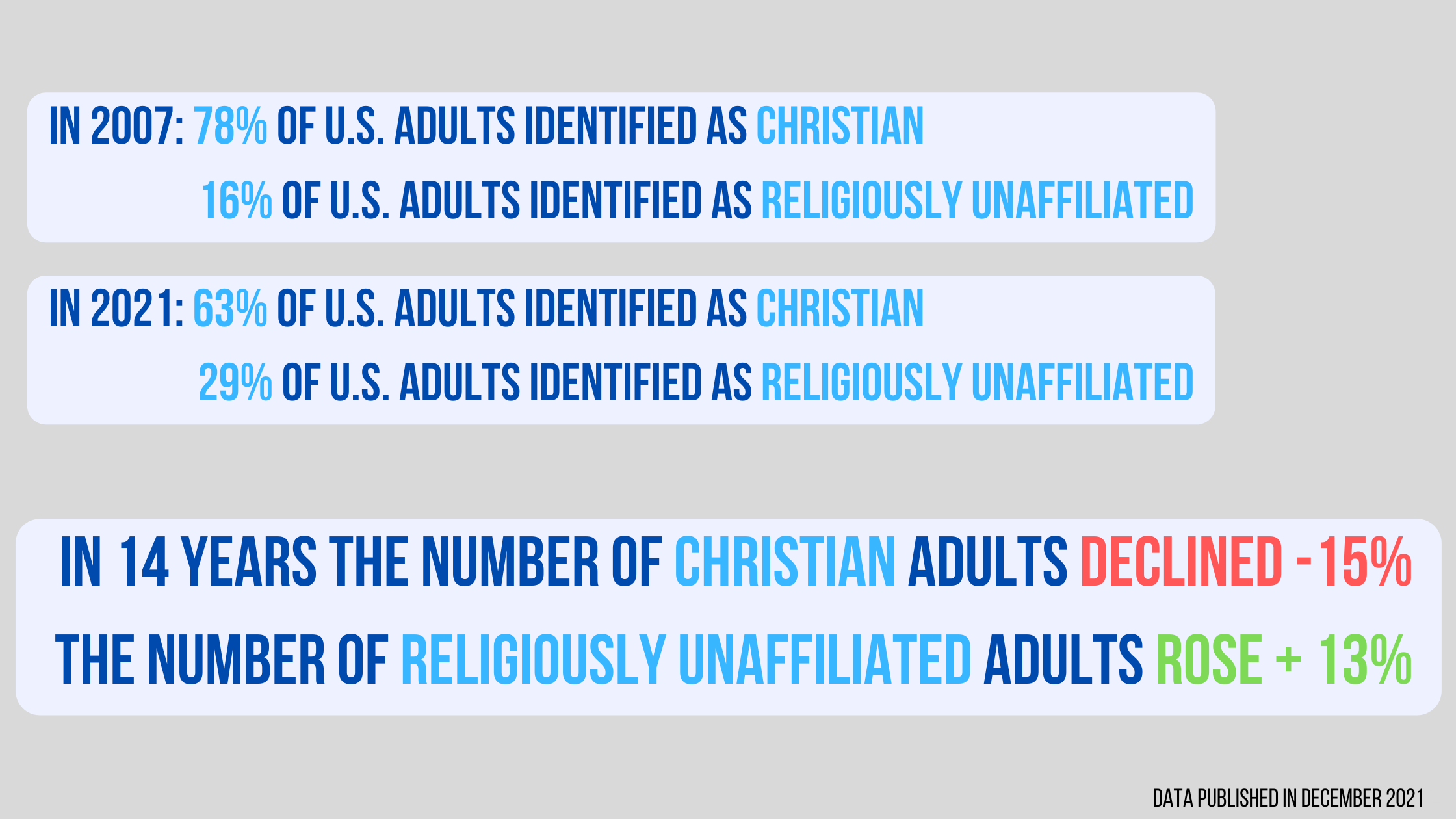

This religious landscape report conducted by the Pew Research Center demonstrates the steady increase of the religiously unaffiliated, or religious “nones.” According to the report, 16% of U.S. adults identified as religious “nones” in 2007, increasing significantly to 29% of U.S. adults in 2021. This report also shows the percentage of Americans who identify as Christian is steadily declining. While 78% of U.S. adults identified as Christian in 2007, only 68% of U.S. adults identified as Christian in 2021. According to Pew’s own analysis, these changes indicate that the “secularizing shifts evident in American society...show no signs of slowing.”

“The American Religious Landscape in 2020,” Public Religion Research Institution, July 8, 2021, https://www.prri.org/research/2020-census-of-american-religion/#page-section-0.

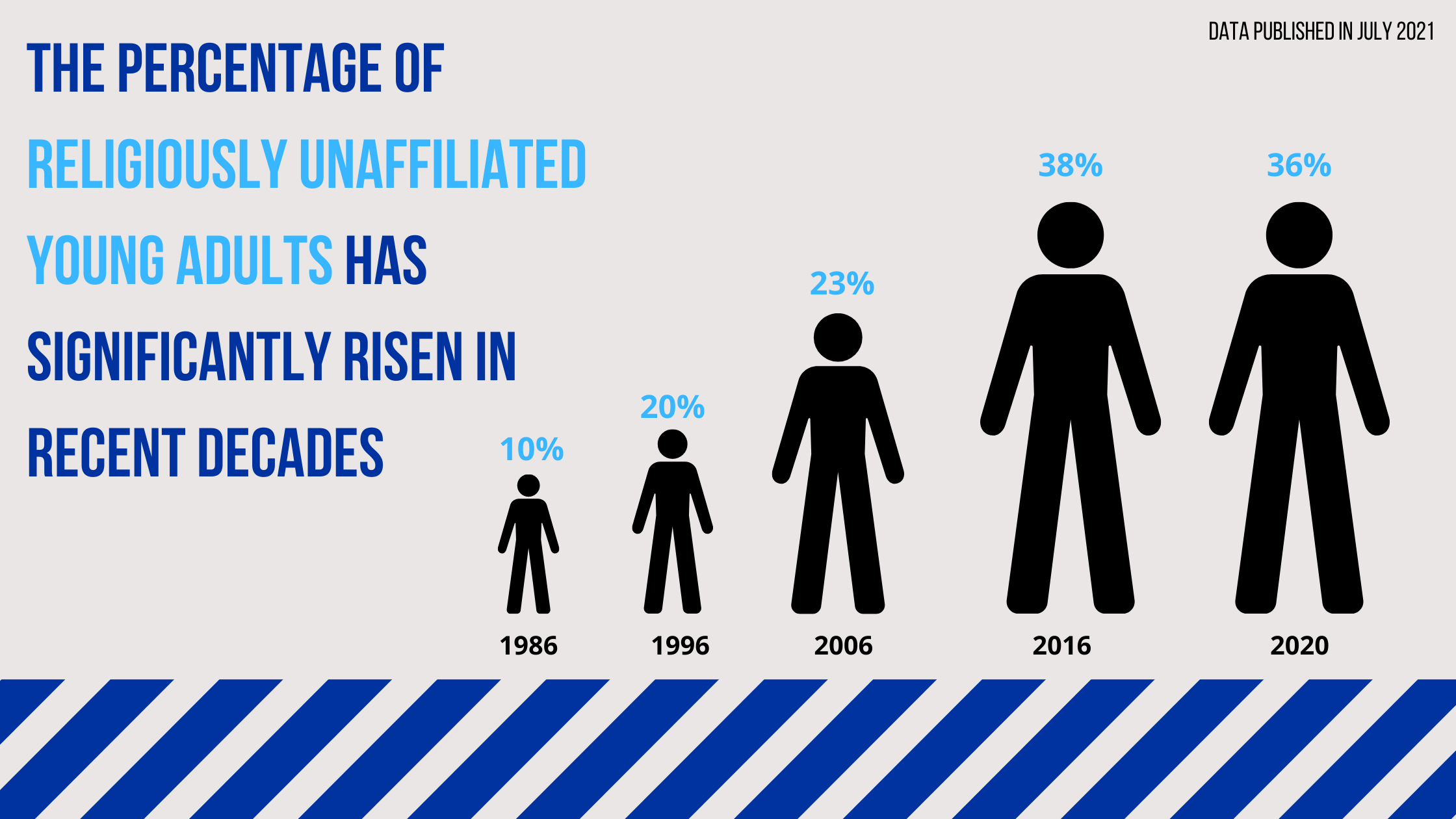

This report from the Public Religion Research Institute found that 36% of young adults (ages 18-29) are religiously unaffiliated in 2021. This percentage has shifted significantly within the past few decades; back in 1986, only 10% of young adults identified as religiously unaffiliated—a 26% difference.. This report does, however, indicate the growth rate of religious “nones” is slowing down and decreased slightly between 2016 and 2020.

Atheists and Secular Humanists are protected by the First Amendment regardless of whether their belief systems are “religions” or not, Washington Post, 2014.

Written by Ilya Somin, law professor at George Mason University, this article considers whether atheism is technically a religion and if that matters in the eyes of the law. Referencing the case American Humanist Association v. U.S. (2014), Somin affirms the court’s ruling that regardless of whether secular humanism is a religion, the establishment clause forbids government discrimination against all types of religious belief including religious unbelief. This same legal principle, Somin contends, extends to the protection of atheists and others “who reject religion or are simply indifferent to it.”

Why it matters that 7 states still have bans on atheists holding office, The Conversation, 2021.

This article examines the significance of a proposed amendment to Tennessee's Constitution that would change the provision barring atheists and ministers from holding office to bar only atheists. Kristina Lee, a doctoral student at Colorado State University, argues this proposal exemplifies the pervasive anti-atheist sentiment in the U.S. Lee traces this sentiment back to early enlightenment thinkers, criticizing John Locke’s condemnation of atheists in his 1689 “Letter Concerning Toleration.” Modern politicians, she argues, are unwilling to take a stand against this discrimination in fear of political pushback. As a result, atheists are further deterred from seeking political office.

“About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Are Now Religiously Unaffiliated,” Pew Research Center, December 14th, 2021, https://www.pewforum.org/2021/12/14/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-are-now-religiously-unaffiliated/.

This graph demonstrates the steady increase of the religiously unaffiliated and the steady decrease of Americans who identify as Christian. This provides a helpful visualization for the U.S.’s changing religious landscape and prompts questions regarding the correlation between the respective rise and fall of religious “nones” and Christians.

“More Young Adults are Unaffiliated Today Than in the Past,” Public Religion Research Institution, July 8, 2021, https://www.prri.org/research/2020-census-of-american-religion/#page-section-0

This chart illustrates the growing percentage of young adults who identify as unaffiliated, beginning in 1986 and ending in 2020. These statistics demonstrate not only the general growth of religious “nones” but also the proportional growth of the demographic within younger generations.

“Faith on the Hill: The religious composition of the 117th Congress,” Pew Research Center, January 4, 2021. https://www.pewforum.org/2021/01/04/faith-on-the-hill-2021/

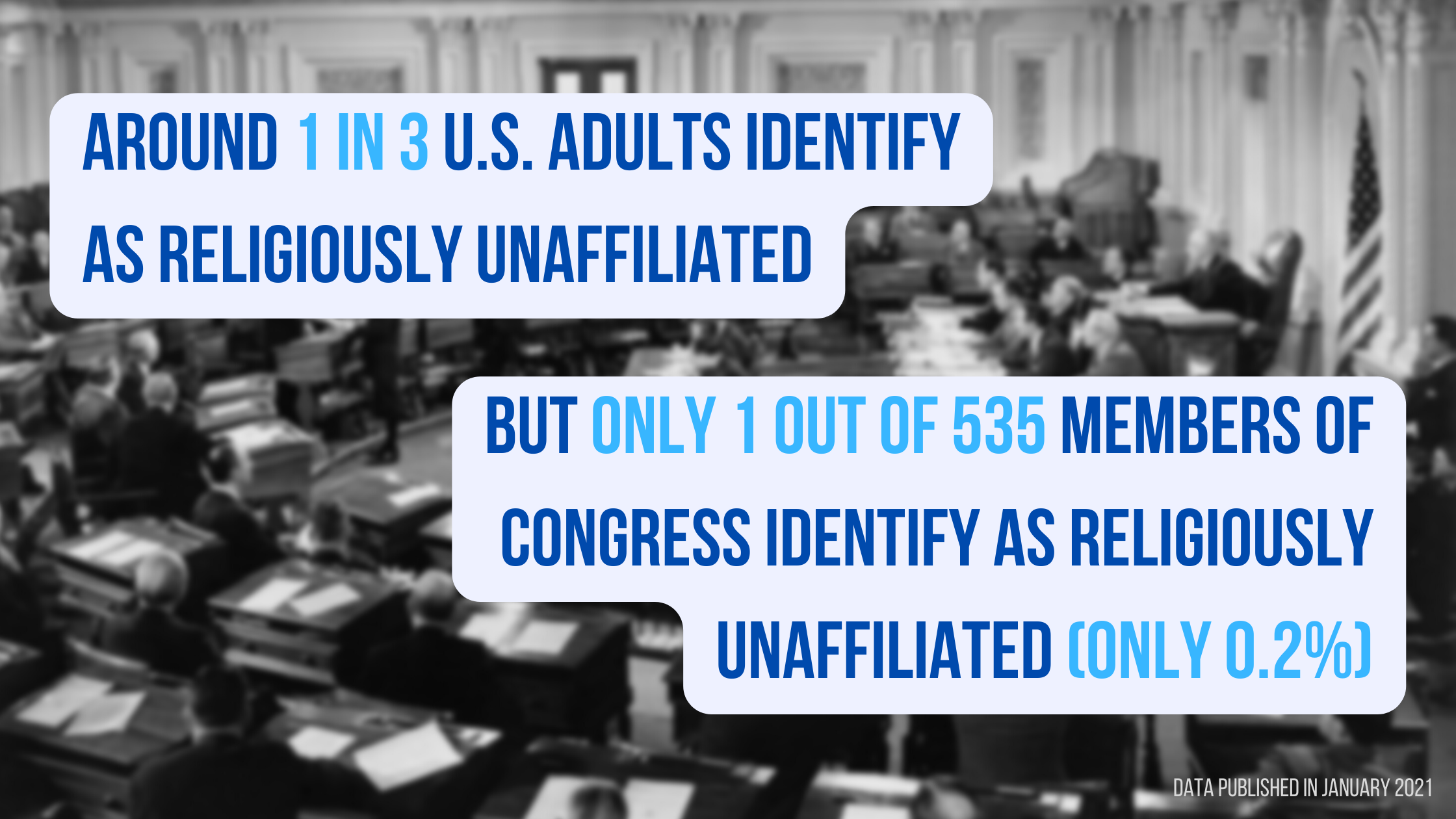

This graphic displays the religious demographics of the 117th Congress, comparing the representation of religious traditions in Congress to their proportional representation among U.S. adults. Notably, there is only one religiously unaffiliated member of Congress. While 26% of Americans are religiously unaffiliated, only 0.2% of Congress identifies with this demographic. This discrepancy offers an entry point to discuss disproportionate religious representation in our government.

Friendly Atheist, “Do These 7 States Really Ban Atheists from Elected Office?,” June 23, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DQ-UAdSH4DU.

In this video Hemant Mehta, an atheist activist, author, and founder of The Friendly Atheist, overviews the seven state bans against atheists in public office and considers their viability. Mehta concludes that while the laws could not actually bar an atheist from running for office, the fact that they remain on the books indicates the anti-atheist sentiment prevalent in U.S. politics. He emphasizes the importance of a religiously diverse body of government and encourages his atheist audience members to consider running for office.

Kurt Karandy, “In Seven States, Atheists Still Barred from Office,” WNYC Studios interview with Jamie Raskin, December 15, 2014 https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/takeaway/segments/atheists

U.S. Representative Jamie Raskin (then a Maryland state senator) is interviewed about the efforts in Maryland to repeal the state’s constitutional ban on atheists serving in public office. He clearly and concisely explains why the language remains in these seven state constitutions despite the Supreme Court’s 1961 decision in Torcaso v. Watkins.

-

Based on content in the video, in what ways does prohibiting religious tests strengthen our democracy? Why might it be important to have a religiously diverse government (including believers and non-believers)?

-

Why is it important that the religious freedom clauses of the First Amendment extend to religious “nones”?

-

Why are there so few religiously unaffiliated people serving in Congress? Beyond the previously discussed laws, what might deter such a person from running for office?

-

Why is the number of religious “nones” growing, especially among younger generations?