Frenzy of the Final Weeks

See how candidates make a final push to sway undecided voters and avoid mistakes that could magnify into embarrassing gaffes in the last weeks of the campaign.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Current Events

- Elections

- Politics

- 6-12

- College/University

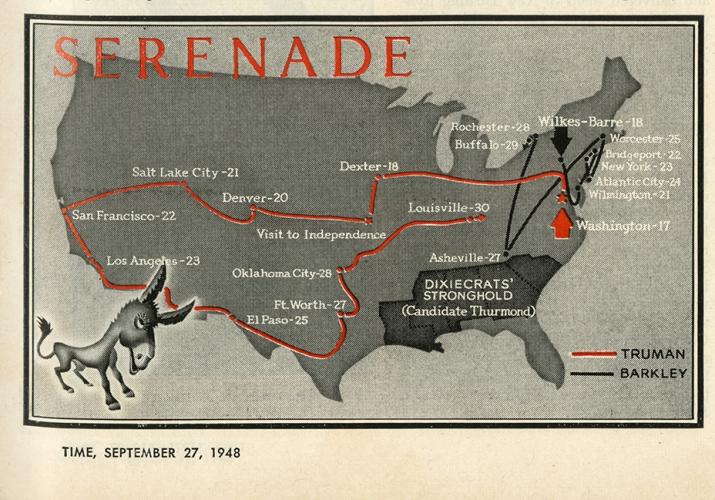

Time magazine recounts the transcontinental journeys of Harry Truman and his running mate, Alben Barkley, in September 1948.

- Ask students what they know about the bumpy road from presidential candidate to party nominee. What steps and events do contenders have to go through?

- This case study is one of four in the Election Procedures section of the Decoding Elections EDCollection that covers: declaring candidacy, competing in primaries and caucuses, being nominated at the national convention, and the final weeks of wooing voters before the general election. Explain that the case study they will be looking at will raise questions about how democratic our presidential election system is.

- Read the Explore the Debate question aloud and/or write it on the board. Read them the overview that sets the scene for group work. Tell them they will use historical and contemporary examples to reach a consensus in small groups on an answer to the debate question.

- Pass out copies of the case study and the Organizing Evidence worksheet. Have the groups read each of the four Election Essentials and use the Questions to Consider to help guide the discussion. They should complete sections 1 and 2 on the worksheet.

- Have the students look at the Pages From History artifacts for the case study on NewseumED.org and complete section 3 on the worksheet. Give the groups 15 minutes to collect and organize information to formulate evidence-supported arguments for their answer to the debate question. (If time is an issue, skip the artifacts or assign as homework.)

- Ask the groups to share their conclusions and reasoning. You may want to use the discussion questions again to push and expand the debate.

- Copies of the case study handout, one per student (download)

- Organizing Evidence worksheet, one per group (download)

- Access to NewseumED.org case study artifacts

- NewseumED Pinterest board of related resources (optional)

Can candidates alter the outcome of an election – either coming from behind or losing their lead – in the final weeks of the campaign?

After securing their party’s nomination, candidates turn their attention to the general election. The final weeks leading up to Election Day can be hectic, filled with nonstop campaigning, large rallies, advertising blitzes and nationally televised debates. Candidates treat this grueling home stretch as extremely important. They focus on finding and winning over undecided voters. They tread carefully to avoid saying or doing anything that might turn into an embarrassing viral gaffe. But despite the intensity of the final weeks of the campaign, it’s not clear whether these last-minute efforts have any real bearing on the Election Day outcome.

1. Who Is Truly Undecided?

Historically, the vast majority of voters make up their mind months before Election Day. In 2012, the number of undecided voters averaged around 6 percent throughout the race. For some undecided voters, party affiliation will ultimately guide their choice. For others, it may take late-breaking news about a major issue like the economy or the candidate to help them decide. For still others, it may come down to a gut decision in the voting booth. Undecideds are unpredictable, and though their number may be small, there are enough of them to have an impact in a tight race.

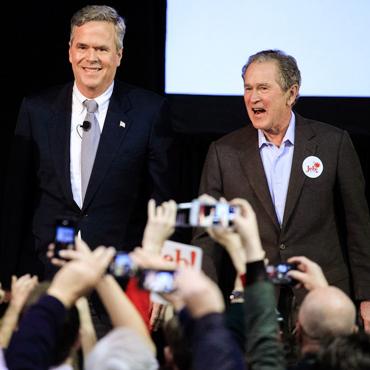

2. Need Votes, Will Travel

The growing importance of the popular vote forced candidates to “run” for office instead of just campaigning from home. They hope face-to-face contact with voters will lock in their support and recharge their enthusiasm to get out the vote in November. In 1948, both incumbent President Harry Truman and Republican challenger Thomas Dewey spent the fall traveling on trains from coast to coast to meet voters. On one trip, Truman traveled for 15 days, covering 8,300 miles. In 2012, President Barack Obama flew 5,300 miles in just one day, heading from the White House to Iowa, Colorado, California and Nevada, then overnight to Florida. Both Truman and Obama were re-elected.

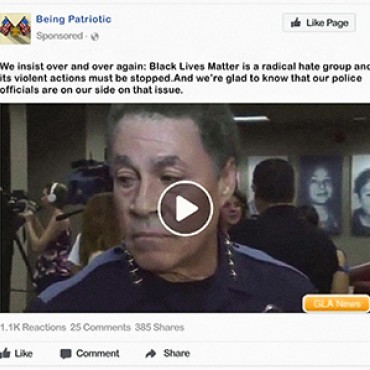

3. No Escape

The media has the power to magnify candidates’ mistakes. In 2012, Republican Mitt Romney was secretly recorded on video saying that 47 percent of Americans would vote for President Obama because they were dependent on the government, and that he could “never convince them that they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives.” Though the comment was said at a private event, the recording made the rounds on social media and through news outlets. Everything candidates say or do has the potential to become fodder for the 24-hour news cycle, especially in the frenzy before Election Day. Gaffes become nearly impossible to escape, and can possibly erode a candidate’s support.

4. Who Will Show Up?

Months of campaigning come down to one crucial issue: voter turnout. After the nominating conventions, campaign operations must focus on get-out-the-vote efforts, because no amount of public support matters if it doesn’t translate into actual votes cast. In recent years, the percentage of total votes cast before Election Day has climbed steadily, from 14 percent in 2000 to nearly 36 percent in 2012. Voters did so by casting absentee ballots, going to the polls early, or voting by mail. As more voters make their selections before Election Day, the final sales pitches by candidates may come too late to make a difference, creating a need for new strategies.

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of face-to-face campaigning?

- National debates involving presidential and vice-presidential candidates are often cast as must-see TV. Do you think these debates change the minds of voters? If so, how? If not, why not?

- Imagine you live in a state where one candidate is projected to win by a landslide. Would this affect whether you vote or whom you vote for?

- What would it take for you to change your mind about a candidate you support?

What’s your political personality type?

What’s your political personality type?

Make Your Voice Matter

Under 18 and can't vote?

Check out other ways to get involved.

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.2

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.6

Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.8

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.2

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

-

NCSS C3 Framework: D2.Civ.3.6-8 and D2.Civ.3.9-12

6 - 8: Examine the origins, purposes, and impact of constitutions, laws, treaties, and international agreements. 9 - 12: Analyze the impact of constitutions, laws, treaties, and international agreements on the maintenance of national and international order.

-

ISTE: 3b. Knowledge Constructor

Students evaluate the accuracy, perspective, credibility and relevance of information, media, data or other resources. -

ISTE: 7d. Global Collaborator

Students explore local and global issues and use collaborative technologies to investigate solutions.

-

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.Historical Thinking.3

A. Compare and contrast differing sets of ideas. B. Consider multiple perspectives. C. Analyze cause-and-effect relationships and multiple causation, including the importance of the individual, the influence of ideas. D. Draw comparisons across eras and regions in order to define enduring issues. E. Distinguish between unsupported expressions of opinion and informed hypotheses grounded in historical evidence. F. Compare competing historical narratives. G. Challenge arguments of historical inevitability. H. Hold interpretations of history as tentative. I. Evaluate major debates among historians. J. Hypothesize the influence of the past. -

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.Historical Thinking.4

A. Formulate historical questions. B. Obtain historical data from a variety of sources. C. Interrogate historical data. D. Identify the gaps in the available records, marshal contextual knowledge and perspectives of the time and place. E. Employ quantitative analysis. F. Support interpretations with historical evidence.

-

National Council of Teachers of English: NCTE.1

Students read a wide range of print and non-print texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works. -

National Council of Teachers of English: NCTE.12

Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.II

A. What is the American idea of constitutional government? B. What are the distinctive characteristics of American society? C. What is American political culture? D. What values and principles are basic to American constitutional democracy?