Can Social Media Be 'Fixed'?

Executives from Twitter, Facebook and Google testified before Congress. Again.

This piece originally appeared in "Inside the First Amendment," a series on First Amendment issues from the Freedom Forum Institute. For more information, contact Lata via email at [email protected], or follow her on Twitter at @LataNott.

This week, executives from Twitter, Facebook and Google testified before Congress. Again. This was the third congressional hearing this year where the internet giants were grilled on their content policies, their privacy and security practices and their role in democracy.

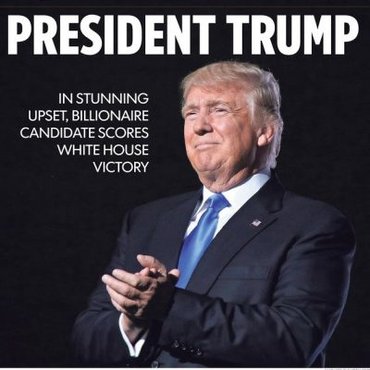

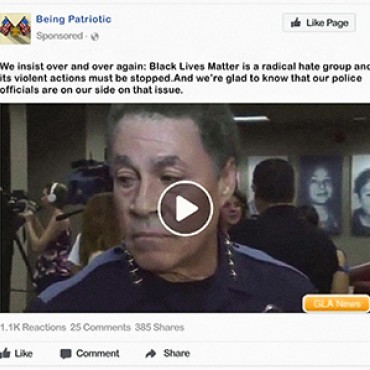

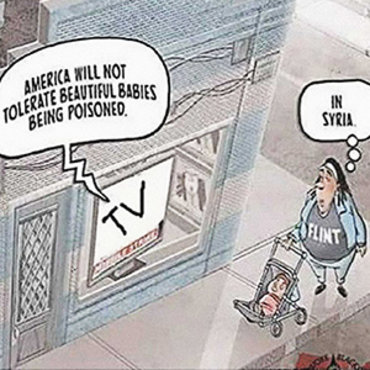

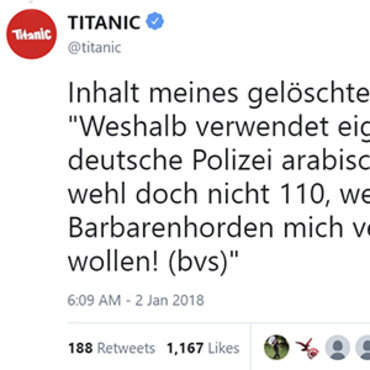

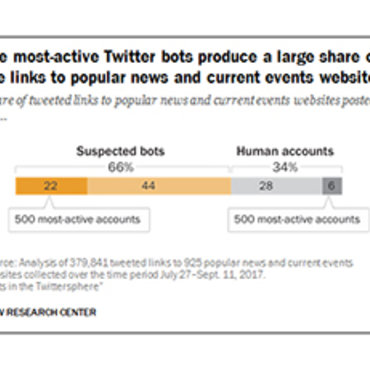

It’s been a rough couple of years for social media platforms. They’ve come under fire for so many different things it can be hard to remember all of them. To recap: For enabling Russian propagandists to influence our presidential election and terrorist organizations to find new recruits. For allowing fake news stories to go viral. For exacerbating political polarization by trapping their users in “filter bubbles.” For giving hate mongers and conspiracy theorists a platform to reach a wider audience. For filtering or down-ranking conservative viewpoints. For collecting private user data and selling it to the highest bidder. For siphoning profits away from struggling local news organizations.

The social media platforms are taking various actions to mitigate these problems. But every potential solution seems to bring forth another unanticipated consequence. YouTube is currently trying to debunk conspiracy videos on its site by displaying links to more accurate information right alongside of them — but there’s concern that the presence of a link to an authoritative source will make a video seem more legitimate, even if the text and link directly contradict the video. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey has expressed a desire to break up his users’ filter bubbles by injecting alternative viewpoints in their feeds. But new research suggests that exposing people to opposing political views may actually cause them to double down on their own— ironically, actually increasing political polarization. Facebook instituted a system for users to flag questionable news stories for review by their fact-checkers — but soon ran into the problem that users would falsely report stories as “fake news” if they disagreed with the premise of the story, or just wanted to target the specific publisher.

Some doubt the sincerity behind these efforts. As former Reddit CEO Ellen Pao says, “[S]ocial media companies and the leaders who run them are rewarded for focusing on reach and engagement, not for positive impact or for protecting subsets of users from harm.” In other words, what’s good for a company’s bottom line and what’s good for society as a whole are often at odds with each other.

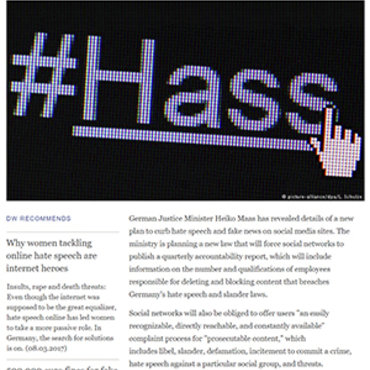

It’s no wonder that the government is looking to step into the fray. If the numerous congressional hearings don’t make that clear, a proposed plan to regulate social media platforms that leaked from Senator Mark Warner’s office last month ought to. Just last week, President Trump announced that he wanted to take action against Google and Twitter for allegedly not displaying conservative media in his search results.

It’s unlikely that the president would be able to do much about that, just as it’s unlikely that Congress would be able to force Facebook to say, ban all fake news stories from its platform. Twitter, Facebook and Google are all private companies, and the First Amendment prohibits government officials from limiting or compelling speech by private actors.

So what can the government do? It can encourage (and, if necessary, regulate) these companies to be more transparent. It’s shocking how little we know about the algorithms, content moderation practices and internal policies that control what information we receive and how we communicate with one another. It’s reckless that we only become aware of these things when something catastrophic happens.