Going for the Jugular

See how attack ads can drown out the promises of positive campaigns. Analyze some of the techniques utilized in campaign ads, and discuss the pros and cons of negative ads from the perspective of candidates and voters.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Current Events

- Elections

- Politics

- 6-12

- College/University

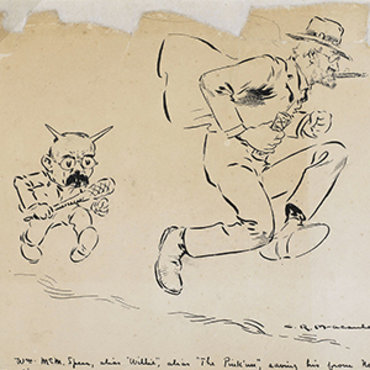

The satirical magazine Puck mocks the Republican Party's dirty tactics in the 1884 presidential campaign and foreshadows its loss.

- Ask students how they hear about campaign news? What sources do they use for updates on the candidates and election events?

- This case study is one of four in the Campaign Messages section of the EDCollection that looks at communication strategies in speeches, news coverage, ads and all-encompassing campaign trail events. Explain that the case study they will be looking at will raise questions about the strengths and weaknesses of each source for the public.

- Read the Explore the Debate question aloud and/or write it on the board. Read them the overview that sets the scene for group work. Tell them they will use historical and contemporary examples to reach a consensus in small groups on an answer to the debate question.

- Pass out copies of the case study and the Organizing Evidence worksheet. Have the groups read each of the four Election Essentials and use the Questions to Consider to help guide the discussion. They should complete sections 1 and 2 on the worksheet.

- Have the students look at the Pages From History artifacts for the case study on NewseumED.org and complete section 3 on the worksheet. Give the groups 15 minutes to collect and organize information to formulate evidence-supported arguments for their answer to the debate question. (If time is an issue, skip the artifacts or assign as homework.)

- Ask the groups to share their conclusions and reasoning. You may want to use the Questions to Consider again to push and expand the debate.

- Copies of the case study handout, one per student (download)

- Organizing Evidence worksheet, one per group (download)

- Access to NewseumED.org case study artifacts

- NewseumED Pinterest board of related resources (optional)

Are negative campaign ads useful sources of information for voters, or distorted representations that alienate the electorate?

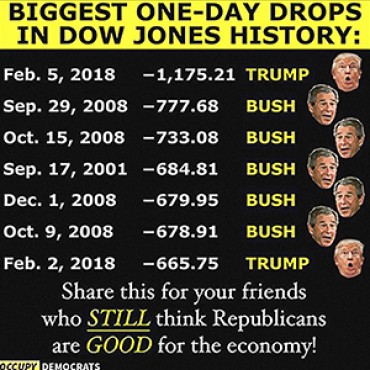

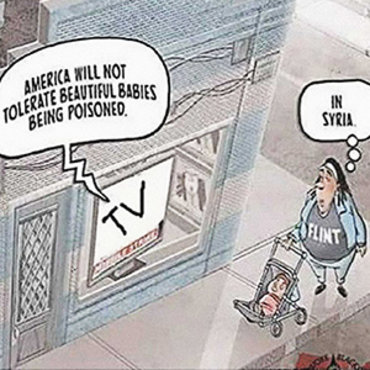

Presidential candidates have always attacked their opponents’ experience, character and credentials, but television – and then the internet – provided a game-changing way of delivering these hits. Even though most viewers say they dislike attack ads, the over-the-top claims, dramatic music and choice visuals raise voters’ emotions, get opponents to engage and attract media attention. Some studies show that attack ads can be effective, particularly when aired close to Election Day. Other studies suggest these ads push people away from the candidates and politics in general. Since there’s no escape from attack ads in tight races, viewers need to see if there’s truth behind the ugly allegations.

1. You’re Corrupt! No, You’re Corrupt!

U.S. politicians have a long history of slinging mud. The bar was set especially low in 1884 when Democrat Grover Cleveland and Republican James G. Blaine faced off. Blaine and his supporters accused Cleveland of being morally corrupt. Cleveland’s supporters responded by claiming Blaine was financially and politically corrupt. In a pre-television era, political cartoonists gleefully amplified the accusations. Voters had to figure out which accusations had facts to back them up and which facts should affect their vote. Cleveland won.

2. Attacked From All Sides

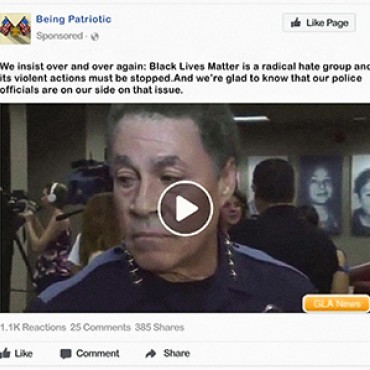

Many of today’s campaign ads are paid for by special interest groups, including super PACs (Political Action Committees), separate from the candidates’ official campaign operations. Super PACs, first created in 2010 after the Supreme Court struck down limits on corporate and labor union political spending, are allowed to raise and spend unlimited money to try to elect or defeat specific candidates as long as they don’t give money directly to the candidate or coordinate their efforts with the candidate’s campaign. Unlike campaign-funded commercials, super PAC ads do not need the candidate to appear and deliver the line required by the Stand By Your Ad provision in a 2002 law: “I’m fill-in-the-blank, and I approved this message.” As a result, some of the campaign’s nastiest attacks come from these groups.

3. Borrowing from the Best

Political strategists have borrowed persuasive techniques from commercial advertising designed to sell things like soap and shoes. For example, their campaign ads may employ the “bandwagon effect,” suggesting everyone’s already on board with these ideas (“Just Do It”). They may appeal to voters’ desire to support a “plain folks” candidate who’s just like them and their distrust of “the elite.” Or, the ads may use “weasel words” that sound more impressive or scary than they really are, such as saying an opponent’s policies could lead to war. Campaign ads have also copied commercials’ careful use of lighting, music and camera angles to create a powerful mood that may or may not reflect reality.

4. Is Anything Off-Limits?

Should a politician’s family members – spouses, parents and children – be fair game for attacks? In 2016, Donald Trump launched an Instagram video highlighting serious allegations made against former president Bill Clinton in 1978, when he was Arkansas’ attorney general. Some Hillary Clinton supporters argued that she should be judged only on her actions and qualifications. Others argued that Bill Clinton’s unique position as a former president who would return to the White House should his wife be elected merited extra scrutiny. Each campaign is free to follow its own standards for what information is or is not fair game for attacks. Voters in turn must decide whether they are comfortable with these standards.

- Why do negative ads rely more on emotional than rational arguments?

- In your experience, are attack ads more effective than positive ads? Compare and contrast the strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

- In today’s media landscape, where do you find campaign ads? What audiences are they targeting?

- Should use of attack ads be regulated? If not, why not? If so, by whom? What should be permissible and what should be off-limits?

1. Go to The Living Room Candidate (www.livingroomcandidate.org) and find a negative/attack ad from a past campaign. Then find one from the current campaign. (Check the candidates’ websites, super PAC websites and/or YouTube.) Make a chart that tracks the source, accusations, visual effects, sound effects/music and persuasive techniques used in each ad. Then write a paragraph comparing and contrasting the two examples and explaining which you think is more effective and why.

2. Elections in the late 20th century ushered in the practice of professional journalists regularly fact-checking ads and candidates’ statements. The first dedicated online site to check political claims for accuracy came in 2004, with FactCheck.org. Others have followed: PolitiFact, NPR’s Fact Check, Washington Post Fact Checker, New York Times Fact Check, and many more. Choose one of these sites (or any from a full list on the Duke Reporters’ Lab). Look at a claim or ad that’s been debunked (proven false). How does the author lay out their case on the item’s validity? Does he or she reference previously published accounts, legitimate studies or statistics, etc.? Do they ask the candidate to respond? If so, what is the response? Write a paragraph about what you read. Explain if you think the author was thorough in his/her analysis, and if the claim should affect your assessment of the candidate.

What’s your political personality type?

What’s your political personality type?

Make Your Voice Matter

Under 18 and can't vote?

Check out other ways to get involved.

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.2

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.6

Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.8

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.2

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

-

ISTE: 3b. Knowledge Constructor

Students evaluate the accuracy, perspective, credibility and relevance of information, media, data or other resources. -

ISTE: 7d. Global Collaborator

Students explore local and global issues and use collaborative technologies to investigate solutions.

-

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.Historical Thinking.3

A. Compare and contrast differing sets of ideas. B. Consider multiple perspectives. C. Analyze cause-and-effect relationships and multiple causation, including the importance of the individual, the influence of ideas. D. Draw comparisons across eras and regions in order to define enduring issues. E. Distinguish between unsupported expressions of opinion and informed hypotheses grounded in historical evidence. F. Compare competing historical narratives. G. Challenge arguments of historical inevitability. H. Hold interpretations of history as tentative. I. Evaluate major debates among historians. J. Hypothesize the influence of the past. -

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.Historical Thinking.4

A. Formulate historical questions. B. Obtain historical data from a variety of sources. C. Interrogate historical data. D. Identify the gaps in the available records, marshal contextual knowledge and perspectives of the time and place. E. Employ quantitative analysis. F. Support interpretations with historical evidence.

-

National Council of Teachers of English: NCTE.1

Students read a wide range of print and non-print texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works. -

National Council of Teachers of English: NCTE.12

Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.II

A. What is the American idea of constitutional government? B. What are the distinctive characteristics of American society? C. What is American political culture? D. What values and principles are basic to American constitutional democracy?