Harnessing the Political Power of Words

See how advisers and speechwriters shape the words of presidential candidates for maximum effect — and evaluate rhetorical techniques that presidential candidates use, with a focus on political slogans.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Current Events

- Elections

- Politics

- 6-12

- College/University

A vendor sells pins to supporters of Democratic contender Hillary Clinton at a May 26, 2016, rally in San Jose, Calif., shortly before that state's primary.

- Ask students how they hear about campaign news? What sources do they use for updates on the candidates and election events?

- This case study is one of four in the Campaign Messages section of the Decoding Elections EDCollection that looks at communication strategies in speeches, news coverage, ads and all-encompassing campaign trail events. Explain that the case study they will be looking at will raise questions about the strengths and weaknesses of each source for the public.

- Read the Explore the Debate question aloud and/or write it on the board. Read them the overview that sets the scene for group work. Tell them they will use historical and contemporary examples to reach a consensus in small groups on an answer to the debate question.

- Pass out copies of the case study and the Organizing Evidence worksheet. Have the groups read each of the four Election Essentials and use the Questions to Consider to help guide the discussion. They should complete sections 1 and 2 on the worksheet.

- Have the students look at the Pages From History artifacts for the case study on NewseumED.org and complete section 3 on the worksheet. Give the groups 15 minutes to collect and organize information to formulate evidence-supported arguments for their answer to the debate question. (If time is an issue, skip the artifacts or assign as homework.)

- Ask the groups to share their conclusions and reasoning. You may want to use the Questions to Consider again to push and expand the debate.

- Copies of the case study handout, one per student (download)

- Organizing Evidence worksheet, one per group (download)

- Access to NewseumED.org case study artifacts

- NewseumED Pinterest board of related resources (optional)

Does presidential candidates’ use of rhetoric, particularly slogans, give voters an easy way to understand and remember their platforms, or does it mislead them?

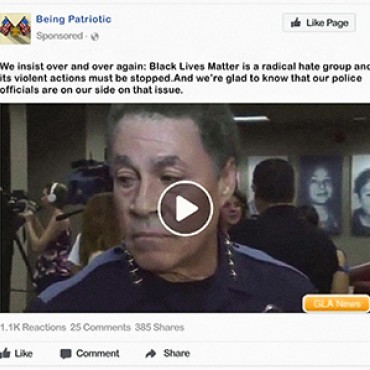

The ability to adapt a complex political platform into a series of memorable statements and catchy phrases has become essential to political success. In an era when attention spans are short, the campaign season is long and the airwaves are crowded, presidential candidates work to package their proposals in a way that will instantly resonate with voters, often relying on rhetoric to convey an idea. Rhetoric – using deliberately crafted words to persuade – has been a campaign tool since the dawn of politics itself, but the specific rhetorical techniques in play have evolved over time. The results are political messages tailor-made for a specific moment, able to reach broad audiences and attract new supporters. But the polished language may fall short of revealing each candidate’s vision and presidential potential.

1. Catchy … but True?

Politicians crafted slogans long before today’s age of sound-bite driven news and social media. In the 1840 election, William Henry Harrison and his running mate, John Tyler, adopted the effective and memorable campaign slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” Tippecanoe was Harrison’s nickname from an 1811 military battle. The Whig Party slogan helped emphasize Harrison’s reputation as a down-home war hero running to bring the people’s voice back to the White House. In fact, Harrison came from a well-established Virginia family and had very expensive tastes that drove him into debt, yet he won the election decisively in the Electoral College.

2. Making Policy Pithy

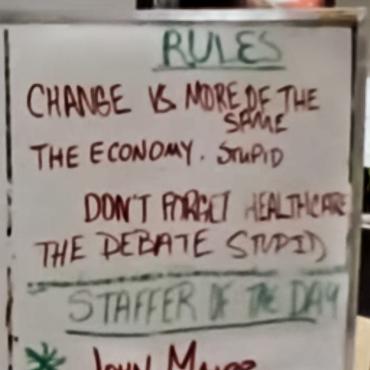

In 1992, Democratic Gov. Bill Clinton of Arkansas was running against incumbent President George H.W. Bush and independent Ross Perot, a Texas businessman. Financial fears weighed heavily on the minds of many voters, but complicated explanations of issues like the federal budget deficit wouldn’t win votes. Many voters weren’t sure how these issues affected their lives. In search of a simpler take, Clinton adviser James Carville coined a phrase to sum up why voters should back Clinton: “The economy, stupid.” It was blunt and lacked specifics, but became famous and successfully painted Clinton as the candidate focused on the economy.

3. Words + Pictures = More Impact

One of Sen. Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign slogans – “Hope” – became popular when it was paired with a now-iconic portrait of Obama by artist Shepard Fairey. The Obama/Hope poster started popping up in cities across the country, plastered alongside advertisements and on the sides of buildings. Then the image began appearing on stickers, clothing and buttons. Obama detractors made their own version of the image, swapping out the H for an N to spell “Nope.” Even if voters could not describe any of Obama’s specific proposals, his name and image became instantly associated with the word and idea of “hope.” Obama defeated Republican Sen. John McCain that November.

4. Recycling Rhetoric

Sometimes a slogan is so appealing and adaptable that it comes back for an encore. Donald Trump’s 2016 slogan, “Make America Great Again,” is very similar to candidate Ronald Reagan’s 36 years earlier. Reagan’s slogan was “Let’s Make America Great Again.” Trump tweeted an old photo of himself with Reagan and the message, “Like Reagan, it’s time to Make America Great Again!,” making it clear he welcomes the comparison. Although Reagan and Trump are both Republicans, in recent history the phrase “make America great again” has been used by politicians on both sides of the aisle to evoke nostalgia and rally patriotism.

- What makes a slogan effective?

- Make a list of advertising slogans you can remember. How do these compare to and contrast with political slogans?

- What rhetorical techniques can you identify politicians using in their speeches and slogans this election? Some techniques to look for: alliteration, repetition, metaphor and simile, questions, hyperbole (exaggeration), etc.

- Have political slogans evolved over time? Explain

Research the platform of a current or past presidential, gubernatorial or congressional candidate, then create a slogan for that person. Write a paragraph explaining why you chose this slogan, including how it reflects the candidate’s platform and why you think it will appeal to voters.

What’s your political personality type?

What’s your political personality type?

Make Your Voice Matter

Under 18 and can't vote?

Check out other ways to get involved.

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.2

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.6

Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.8

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.2

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

-

ISTE: 3b. Knowledge Constructor

Students evaluate the accuracy, perspective, credibility and relevance of information, media, data or other resources. -

ISTE: 7d. Global Collaborator

Students explore local and global issues and use collaborative technologies to investigate solutions.

-

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.US History.Era 3

Standard 1: The causes of the American Revolution, the ideas and interests involved in forging the revolutionary movement, and the reasons for the American victory Standard 2: The impact of the American Revolution on politics, economy, and society Standard 3: The institutions and practices of government created during the Revolution and how they were revised between 1787 and 1815 to create the foundation of the American political system based on the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights -

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.US History.Era 4

Standard 1: United States territorial expansion between 1801 and 1861, and how it affected relations with external powers and Native Americans Standard 2: How the industrial revolution, increasing immigration, the rapid expansion of slavery, and the westward movement changed the lives of Americans and led toward regional tensions Standard 3: The extension, restriction, and reorganization of political democracy after 1800 Standard 4: The sources and character of cultural, religious, and social reform movements in the antebellum period

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.II

A. What is the American idea of constitutional government? B. What are the distinctive characteristics of American society? C. What is American political culture? D. What values and principles are basic to American constitutional democracy?