Public Participation Goes Viral

See how social media revolutionized how the public and candidates interact — and evaluate how it affects political campaigns.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Current Events

- Elections

- Politics

- 6-12

- College/University

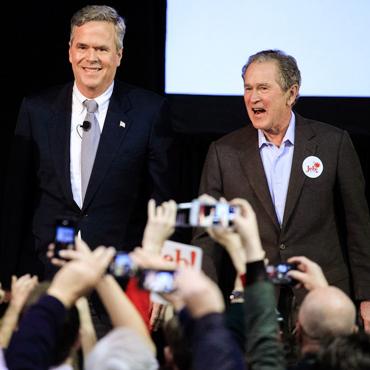

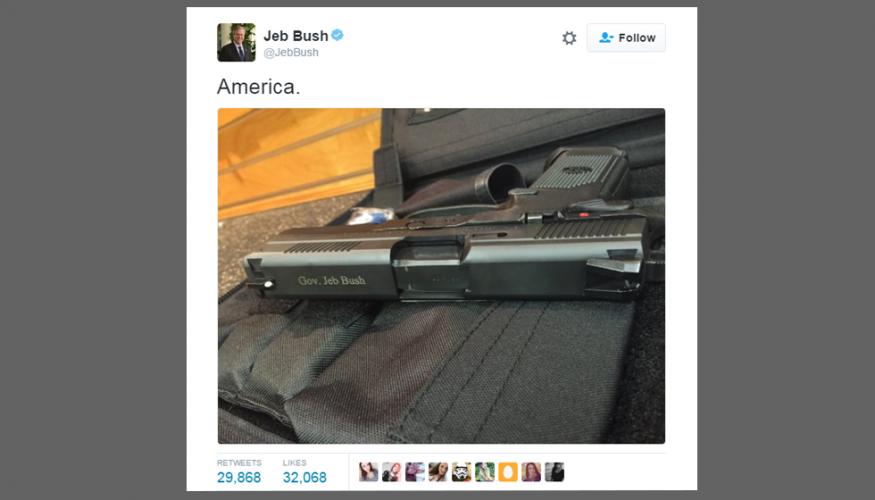

This Feb. 16, 2016, tweet by Republican presidential contender Jeb Bush sparked backlash and parodies online.

- Ask students to brainstorm all the ways the public is involved in the election process. Can individuals make a difference?

- This case study is one of three in the Public Participation section of the Decoding Elections EDCollection that looks at the use of social media, campaign events and efforts to change a political process that some consider unfair. Explain that the case study they will be looking at will raise questions about efficacy of public engagement in the election process.

- Read the Up for Debate question aloud and/or write it on the board. Read the students the overview that sets the scene for group work. Tell them they will use historical and contemporary examples to reach a consensus in small groups on an answer to the debate question.

- Pass out copies of the case study and the Organizing Evidence worksheet. Have the groups read each of the four Election Essentials and use the Questions to Consider to help guide the discussion. They should complete sections 1 and 2 on the worksheet.

- Have the students look at the Pages From History artifacts for the case study on NewseumED.org and complete section 3 on the worksheet. Give the groups 15 minutes to collect and organize information to formulate evidence-supported arguments for their answer to the debate question. (If time is an issue, skip the artifacts or assign as homework.)

- Ask the groups to share their conclusions and reasoning. You may want to use the Questions to Consider again to push and expand the debate.

- Copies of the case study handout, one per student (download)

- Organizing Evidence worksheet, one per group (download)

- Access to NewseumED.org case study artifacts

- NewseumED Pinterest board of related resources (optional)

Has social media changed presidential campaigns for better or worse?

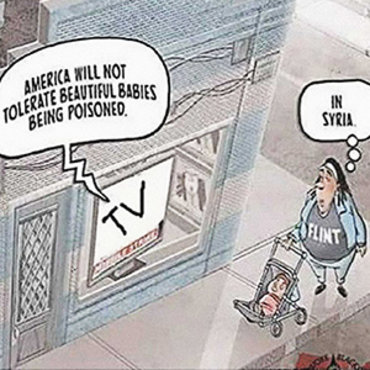

While candidates are crisscrossing the country and honing their message, their campaign teams look closely at how it resonates with voters and how to maximize its reach. Social media is a key tool in this process, and it has changed the game for voters, too. Social media allows members of the public to respond swiftly to every event and message and to get involved in campaigns from the comfort of their own home. But is all of this communication deepening knowledge of the candidates and empowering voters, or is it just another distraction littered with misleading messages?

1. Going Digital

Before the internet existed, voters built social networks to support candidates – they just did so locally, and in person, as in the Hickory Clubs for Democrat Andrew Jackson in 1828 and the Willkie Clubs for GOP candidate Wendell Willkie in 1940. In 1996, the World Wide Web was first used in campaigning and fundraising, but it was Democratic candidate Gov. Howard Dean in 2004 who harnessed the power of internet to build a political community. His campaign used blogs, the social networking tool Meetup and the customized platform DeanLink to mobilize and connect supporters. The response shaped Dean’s messaging, as he explained: “If I give a speech and the blog people don't like it, next time I change the speech."

2. Reaching Young Voters

During the 2008 election, Democratic contender Barack Obama capitalized on millennials’ technology such as Facebook and YouTube to reach out to them and energize supporters. This strategy paid off. On election night, Obama won 66 percent of voters under age 30. Public participation on social media gave Obama free promotion and led to grass-roots organizing on his behalf by people outside the official campaign operation. In exchange for relinquishing some control, the campaign saved time and money and broadened its reach.

3. More Platforms, More Impact?

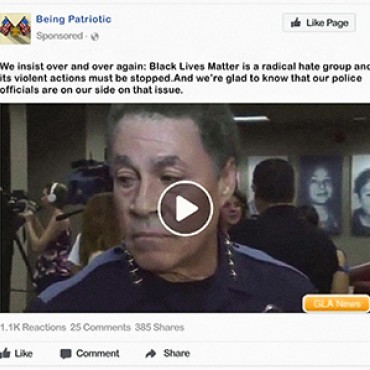

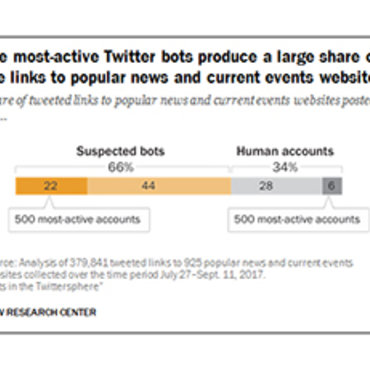

When Obama campaigned in 2008, 25 percent of all adults used social media. By 2015, 65 percent used it, making online efforts more important than ever for political campaigning. The number of widely adopted social media platforms had grown, too, to include Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat and more. As a result, candidates try to use multiple social media platforms, and create more opportunities for voters to respond to them. In 2015, Facebook users posted more than 1 billion comments about the election. Campaigns now have incredibly detailed data about who they are reaching and can create targeted ads, but how to convert the data into votes is still uncertain.

4. Commandeering the Story

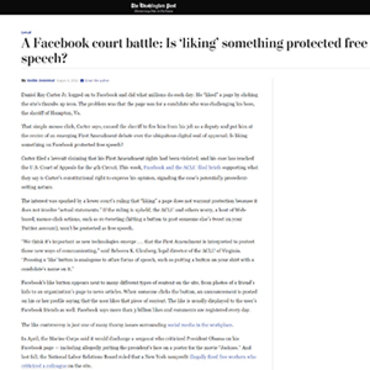

Tweeting and using hashtags let candidates for all levels of political office get visibility, but it doesn’t guarantee they can control the messaging. During the 2016 campaign, Republican candidate Jeb Bush tweeted a photograph of his new monogrammed gun with the caption “America,” hoping to connect with gun users in the GOP base. Twitter users’s responses ranged from parodies to political statements to personal attacks. On the Democratic side, when Hillary Clinton became the presumptive nominee, dejected Bernie Sanders’s supporters expressed their weak enthusiasm for her candidacy by using the hashtag #IGuessImWithHer, a play on Clinton’s #ImWithHer campaign slogan.

- How has the development of social media changed the election process?

- When does digital political engagement benefit the voters and the election process? When does it hurt?

- Who, if anyone, controls campaign content on social media? Can candidates be sure their messages will not be altered?

- Do voters’ social media posts have a real impact? If yes, how so? If not, why not? How do you know?

- What does productive political engagement look like on social media?

Research any election prior to 2004 and think about how the existence and use of social media might have changed that election. Find a slogan, speech or object of persuasion for two of the candidates that year and remix them into social media posts for two different platforms (Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, etc.).

What’s your political personality type?

What’s your political personality type?

Make Your Voice Matter

Under 18 and can't vote?

Check out other ways to get involved.

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.2

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.2

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

-

NCSS C3 Framework: D2.Civ.3.6-8 and D2.Civ.3.9-12

6 - 8: Examine the origins, purposes, and impact of constitutions, laws, treaties, and international agreements. 9 - 12: Analyze the impact of constitutions, laws, treaties, and international agreements on the maintenance of national and international order. -

NCSS C3 Framework: D4.1.6-8 and D4.1.9-12

6 - 8: Construct arguments using claims and evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging the strengths and limitations of the arguments. 9 - 12: Construct arguments using precise and knowledgeable claims, with evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging counterclaims and evidentiary weaknesses.

-

ISTE: 3d. Knowledge Constructor

Students build knowledge by actively exploring real-world issues and problems. -

ISTE: 7d. Global Collaborator

Students explore local and global issues and use collaborative technologies to investigate solutions.

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.II

A. What is the American idea of constitutional government? B. What are the distinctive characteristics of American society? C. What is American political culture? D. What values and principles are basic to American constitutional democracy?