Too Many Candidates vs. Too Few

Explore the role of third-party candidates and how the American political system makes it very difficult for anyone outside the Republican or Democratic Party to win the White House.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Elections

- Politics

- 6-12

- College/University

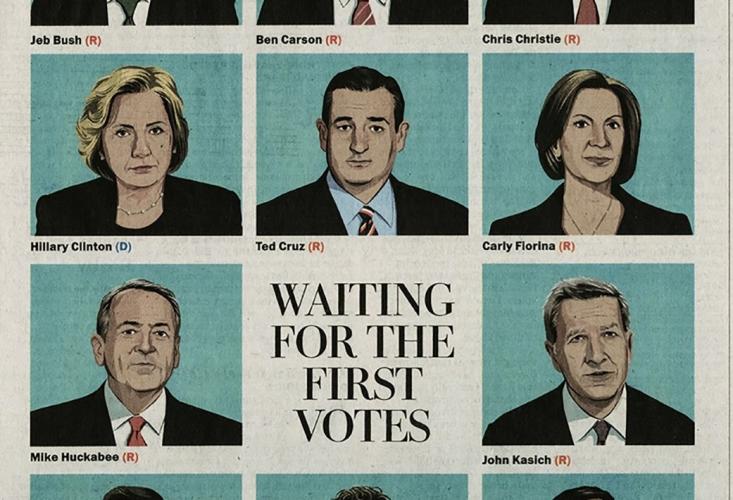

The illustration in The Washington Post of Democratic and Republican candidates in 2016 shows a diverse and crowded field of hopefuls for the two major parties.

- Ask students what they know about the bumpy road from presidential candidate to party nominee. What steps and events do contenders have to go through?

- This case study is one of four in the Election Procedures section of the Decoding Elections EDCollection that covers: declaring candidacy, competing in primaries and caucuses, being nominated at the national convention, and the final weeks of wooing voters before the general election. Explain that the case study they will be looking at will raise questions about how democratic our presidential election system is.

- Read the Explore the Debate question aloud and/or write it on the board. Read them the overview that sets the scene for group work. Tell them they will use historical and contemporary examples to reach a consensus in small groups on an answer to the debate question.

- Pass out copies of the case study and the Organizing Evidence worksheet. Have the groups read each of the four Election Essentials and use the Questions to Consider to help guide the discussion. They should complete sections 1 and 2 on the worksheet.

- Have the students look at the Pages From History artifacts for the case study on NewseumED.org and complete section 3 on the worksheet. Give the groups 15 minutes to collect and organize information to formulate evidence-supported arguments for their answer to the debate question. (If time is an issue, skip the artifacts or assign as homework.)

- Ask the groups to share their conclusions and reasoning. You may want to use the Questions to Consider again to push and expand the debate.

- Copies of the case study handout, one per student (download)

- Organizing Evidence worksheet, one per group (download)

- Access to NewseumED.org case study

- NewseumED Pinterest board of related resources (optional)

When it comes time to elect the next leader, do voters have a viable choice besides the two major-party nominees?

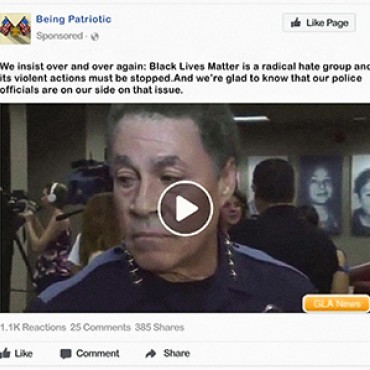

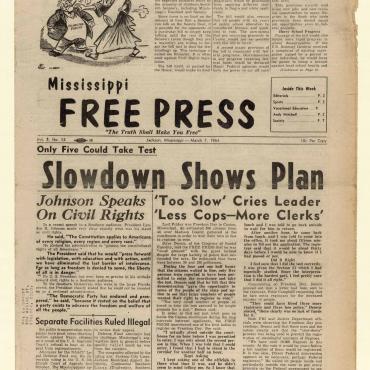

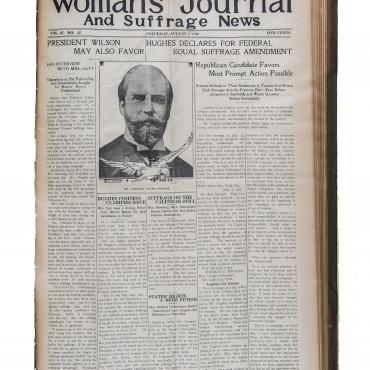

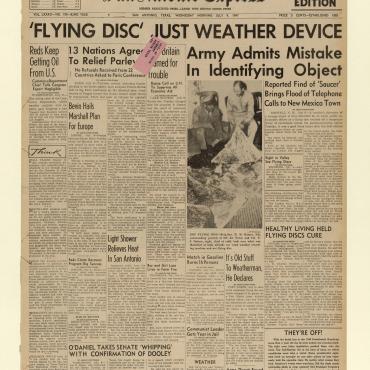

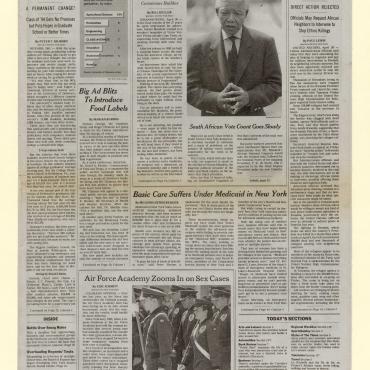

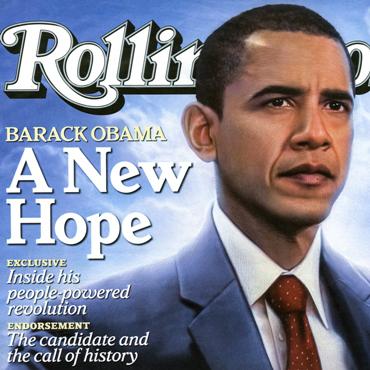

Since 1980, nearly 2,500 people have filed the requisite paperwork to run for president. In the 2016 election, nearly 1,800 people filed the basic form, from Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump to “Captain Crunch” and “Buddy the Cat.” However, most news media quickly focused on the 22 most prominent contenders for the Democratic and Republican nominations. The primary season became a struggle for each individual to be heard within their party and separate themselves from the pack, while citizens tried to figure out who best represented their own views. On the Republican side, an unusually large field of 17 candidates proved too many to fit on a single debate stage, forcing debate hosts to rank and divide the contenders. Lower-ranked Republican Party candidates got less desirable times for connecting with viewers, while third-party candidates got none. Historically, by the time Election Day arrives, most voters only recognize the two major party candidates.

1. Getting in the Race

The only constitutional requirements to be president are: be a natural-born citizen, at least 35 years old and a resident of the United States for at least 14 years. But even people who don’t meet these basic requirements (or, for that matter, animals and fictional characters) can file paperwork to run for president and appear on the Federal Election Commission’s online list of declared candidates. It is the next steps — filing an official “statement of organization” and getting on the ballot in each state — that take time and money and separate serious candidates from “Yoda For Prez.”

2. When Parties Fracture

In 1860, the United States was deeply divided over the issue of slavery, and this division played out in its political parties as the presidential election neared. Northern and Southern Democrats were unable to agree on a candidate, and wound up splitting into two factions, with Northerners nominating Stephen A. Douglas and Southerners nominating John C. Breckinridge. Other politicians hoped to avoid the slavery conflict altogether and formed the Constitutional Union Party with John Bell as their nominee. This chaos enabled the Republican nominee, Abraham Lincoln, to take the White House despite winning less than half of the popular vote and not a single Southern state.

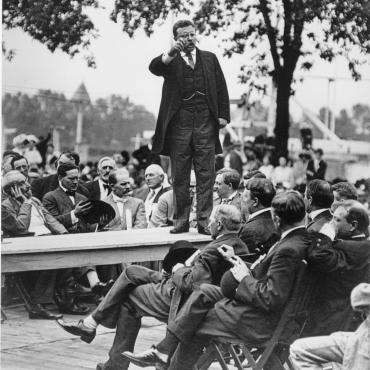

3. Third Party Potential?

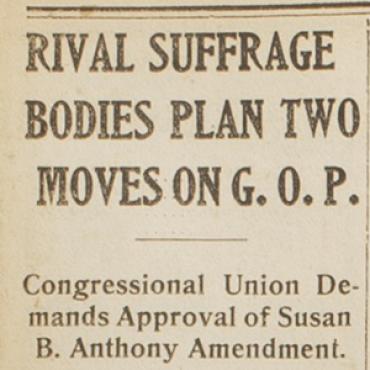

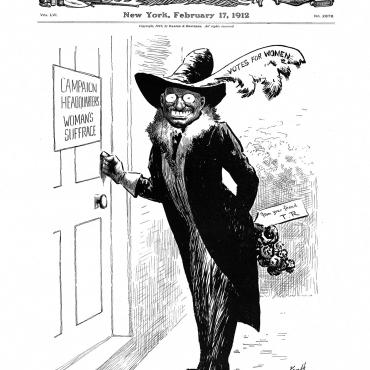

Since the Civil War, a Democrat or Republican has won every presidential election. Only a few times have third-party candidates (candidates who are not Democrats or Republicans but have enough money and support to run a campaign) garnered much popular support. Notable examples include Theodore Roosevelt for the Progressive (“Bull Moose”) Party in 1912 and Ross Perot in 1992 as an independent. Third-party candidates can influence elections by shifting support away from a major-party candidate. In 2000, George W. Bush won Florida and the presidency by only 537 votes. Political commentators have speculated that third-party candidates — who won more than 130,000 votes in Florida — swayed the election.

4. Is There Another Way?

Not all democracies have a two-party system of government. In Germany, multiple political parties are currently represented in the Bundestag, the directly elected house of the national legislature. No party has a majority, so they must join together and form coalitions in order to pass laws. Germany’s constitution also calls for the Bundestag to elect the head of the government, or chancellor, rather than holding a direct election by citizens. The leader may come from any of the parties represented in the Bundestag, but must earn support from other parties, as well, to win the top spot.

- Should third-party candidates be invited to participate in debates? If so, what requirements should they meet to be accepted?

- What challenges do you face when choosing a presidential candidate to support? How do these challenges differ before and after the major parties select their nominees?

- Does a crowded field help or hurt lesser-known candidates running for a major-party nomination?

- What are the alternatives to a two-party system? Is the U.S. system ever likely to change?

- Should third parties – such as the Green Party or the Libertarian Party – get more media attention? Why or why not?

- What are the positives and negatives of the two-party system?

What personality traits and political policies are most important for a candidate seeking political office? Create a checklist of what you look for when deciding on a candidate. Break the list into sections: personality, policy goals and experience. Create a Google document or spreadsheet and track two candidates – one major-party candidate and one third-party candidate – for one week to determine whether they meet your standards.

What’s your political personality type?

What’s your political personality type?

Make Your Voice Matter

Under 18 and can't vote?

Check out other ways to get involved.

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

-

NCSS C3 Framework: D4.1.6-8 and D4.1.9-12

6 - 8: Construct arguments using claims and evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging the strengths and limitations of the arguments. 9 - 12: Construct arguments using precise and knowledgeable claims, with evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging counterclaims and evidentiary weaknesses.

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.II

A. What is the American idea of constitutional government? B. What are the distinctive characteristics of American society? C. What is American political culture? D. What values and principles are basic to American constitutional democracy?