Primaries: By Invitation Only?

Primary season can be a wild ride. See how the primary process works as voters narrow the field of candidates in contest after contest, while the parties use complicated rules to try to control who ultimately secures the nomination.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Elections

- Politics

- 6-12

- College/University

In the Republican primaries for the 2016 presidential election, there were too many candidates to fit on one stage in Cleveland. Ten debated on prime-time television, while seven others faced off earlier.

- Ask students what they know about the bumpy road from presidential candidate to party nominee. What steps and events do contenders have to go through?

- This case study is one of four in the Election Procedures section of the Decoding Elections EDCollection that covers: declaring candidacy, competing in primaries and caucuses, being nominated at the national convention, and the final weeks of wooing voters before the general election. Explain that the case study they will be looking at will raise questions about how democratic our presidential election system is.

- Read the Explore the Debate question aloud and/or write it on the board. Read them the overview that sets the scene for group work. Tell them they will use historical and contemporary examples to reach a consensus in small groups on an answer to the debate question.

- Pass out copies of the case study and the Organizing Evidence worksheet. Have the groups read each of the four Election Essentials and use the Questions to Consider to help guide the discussion. They should complete sections 1 and 2 on the worksheet.

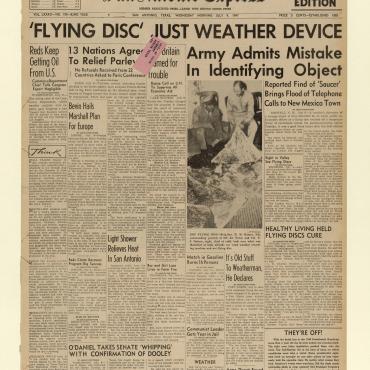

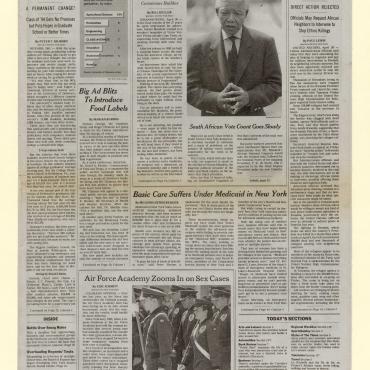

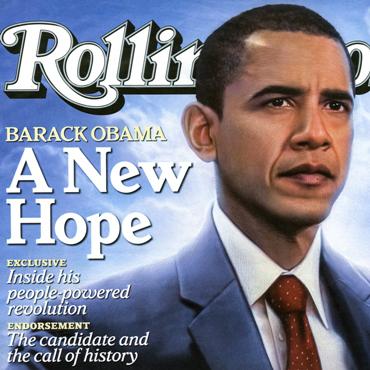

- Have the students look at the Pages From History artifacts for the case study on NewseumED.org and complete section 3 on the worksheet. Give the groups 15 minutes to collect and organize information to formulate evidence-supported arguments for their answer to the debate question. (If time is an issue, skip the artifacts or assign as homework.)

- Ask the groups to share their conclusions and reasoning. You may want to use the Questions to Consider again to push and expand the debate.

- Copies of the case study handout, one per student (download)

- Organizing Evidence worksheet, one per group (download)

- Access to NewseumED.org case study artifacts

- NewseumED Pinterest board of related resources (optional)

How democratic are the current primary processes? Do the results reflect the will of the people who cast votes or of the party leaders who make the rules?

In today’s presidential election cycle, the road to the White House winds through five months of primaries and caucuses, as candidates vie to represent the two major parties in American politics. Primary season brings a tug-of-war between competing goals and forces. Individual candidates try to attract as much attention and support as possible through television ads, interviews, personal appearances, debates and social media. They may look for opportunities to bend the rules of the race in their favor. Voters try to sort through all the noise, with those who live in states with early contests facing an especially overwhelming onslaught of campaign ads and candidate pressure. Those who vote in later primaries may feel forgotten or discounted. And party leaders – the architects of the primary processes – weigh their options as they watch the primary elections play out either as they’d hoped or as they’d feared.

1. First Efforts

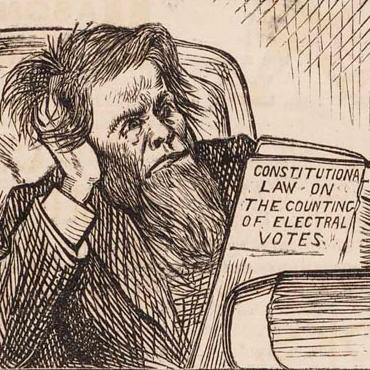

Finding a system for selecting nominees for U.S. president has evolved through trial and error. In the early years of the republic, party caucuses in Congress held complete control over who would represent them in the national election. After pressure in the late 1820s to give a voice to the common man, party members added meetings at local, state and national levels to arrive at a nominee. Attendees were still a select and tightly controlled group of party insiders. Today, parties continue to tweak the rules as each seeks to select a nominee that meets the needs of the public and the party.

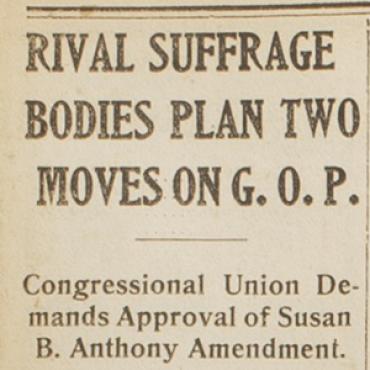

2. Voters Get a Voice … Sort of

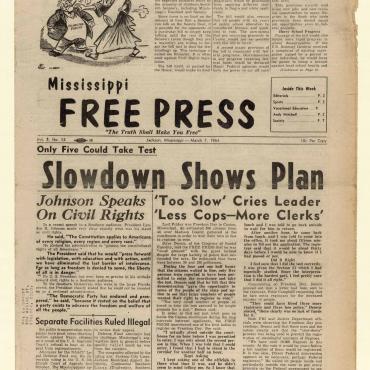

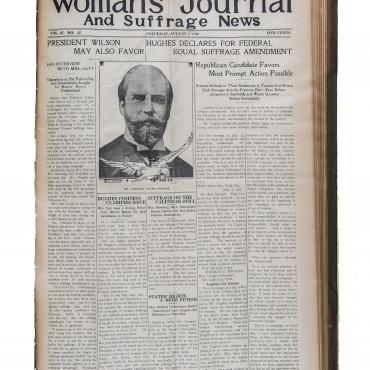

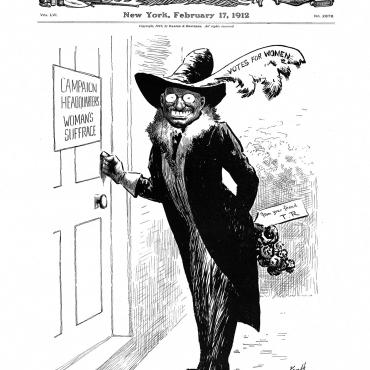

In the early 20th century, states began holding primaries, giving voters a chance to weigh in on the party nominees for president and decreasing the power of the party bosses. Other states chose to hold caucuses, similar to the local and state party meetings that had taken place throughout much of American history. But these first primaries, while opening participation to more voters, were far from fully democratic. Their results were only advisory, meant to help the party reach a consensus on the nominee. In many states, only men could vote, while in the South, many primaries were limited to white voters.

3. Does the Early Bird Get the Nomination?

In 1968, the Democratic nominee for president was Vice President Hubert Humphrey, a late-entry candidate who did not enter a single primary. This angered many Democrats and prompted both parties to adopt a formal delegate system, in which party representatives (delegates) to the national convention pledge to support a candidate based on the results of their home state’s primary election. The result of this change has been more interest and participation in primary elections, with candidates focused on big states and multiple primary days such as “Super Tuesday” to rack up lots of delegates and lock up the nomination before the national convention. Democratic delegates are divided proportionally according to state primary results, while Republican rules allow for winner-take-all contests.

4. Superdelegate Superpowers

Both Republican and Democratic rules allow for a certain number of unpledged delegates, so-called superdelegates, who aren’t bound to support a candidate based on their state primary results. Superdelegates are party elites, typically elected officials or those with longstanding ties and contributions to the party. They were created to balance voters’ preferences based on their inside knowledge or personal history with the candidates. Candidates can try to woo superdelegates to solidify their support, but using their votes to change the nomination – technically possible in the Democratic Party – would likely lead to a backlash from the party base.

- How can political parties, candidates and voters influence primary elections and the nomination?

- Should all primary contests be held on the same day, or over a shorter span of time than the current five months? Why or why not?

- Does the delegate system help or hurt the candidates? The parties? Americans generally?

- Should non-party members be able to vote in primary contests (called open primaries)?

- Should parties have more or less control over the nominating process? How else could candidates be chosen? For example, what if there were a national primary for all candidates of every party with the top two vote-getters facing each other in the general election?

Investigate a proposed change to the 2020 presidential primaries. Research the reasons for and against the change, and their potential impact. Then, explain why you support the change or not.

What’s your political personality type?

What’s your political personality type?

Make Your Voice Matter

Under 18 and can't vote?

Check out other ways to get involved.

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

-

NCSS C3 Framework: D4.1.6-8 and D4.1.9-12

6 - 8: Construct arguments using claims and evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging the strengths and limitations of the arguments. 9 - 12: Construct arguments using precise and knowledgeable claims, with evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging counterclaims and evidentiary weaknesses.

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.II

A. What is the American idea of constitutional government? B. What are the distinctive characteristics of American society? C. What is American political culture? D. What values and principles are basic to American constitutional democracy?