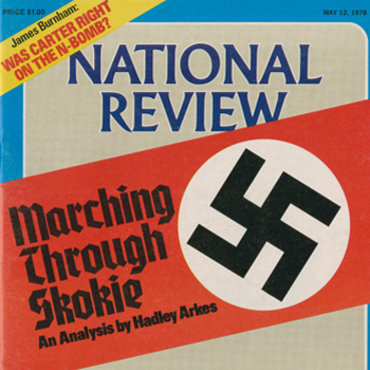

1977: Marching With Symbols of Hate

Should the First Amendment protect protests by groups with a history of displaying racist imagery and promoting racial hatred?

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

This Critical Debate is part of a Debate Comparison:

See all Debate Comparisons- Constitution

- Protests

- Supreme Court

- 7-12

- College/University

Do your students know what they’re free to say online? At school? On a public street corner?

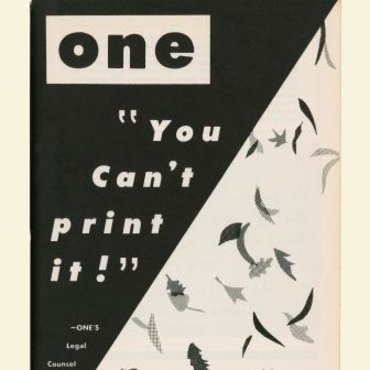

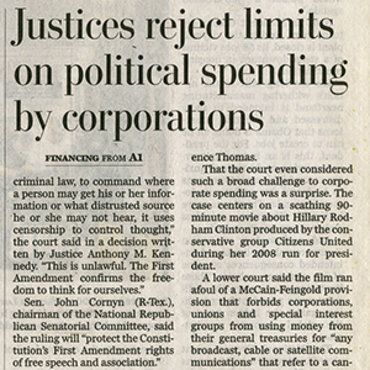

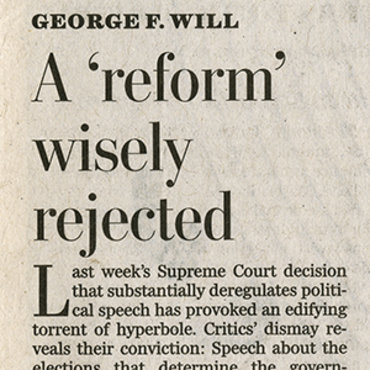

From censorship to cyberbullying, the First Amendment and the freedoms it protects are as hotly contested as ever. This case study is part of our EDCollection that explores 16 real free speech debates ranging from the founding of our nation to recent headlines to illustrate what free speech actually means, where it comes from, and how far it can go. It’s information everyone needs to voice their opinions and shape our society.

Using This EDCollection

This EDCollection is designed to meet the needs of a wide range of circumstances and curricula. Whether you’re a social studies teacher looking for a complete unit or an English teacher looking to spend a single class period on free expression, there’s something for everyone. This complete package will lead students to the outcomes below.

Build Fact-Based Arguments

The Free Speech Essentials curriculum aligns with state and national standards as it guides students to take a position, find evidence to support it, and make a compelling presentation to their peers. Potential evidence includes:

- Writings, images and video from 1787 to 2018

- Primary and secondary sources

Connect Past and Present

Six of the eight pairs of case studies in this EDCollection juxtapose real historical and contemporary debates on a key free expression question. These pairs allow students to explore the historical origins of a key question — and get context for tackling today’s hot-button issues. The other two pairs provide different perspectives on a contemporary issue. Topics include:

- Federalism and Facebook

- Presidents and the press

- Censorship and cyberbullying

Keep Calm (and Debate On)

Our case studies are structured to help students experience the passion of the real players, while still practicing productive debate. We provide everything you need to prepare and fully support your students as they engage in civil discourse and debates:

- Overviews of the outcomes

- Clear scenarios and suggested positions

- Suggested discussion prompts.

Today’s social and political landscape can sometimes make free speech and First Amendment controversies seem too explosive for classroom exploration. We’ve created Free Speech Essentials to give you the tools you need to start tackling these vital topics with confidence and create enriching experiences for your students.

— The NewseumED Team

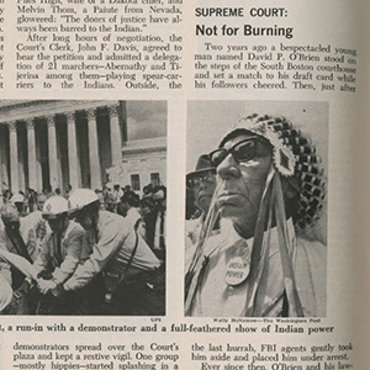

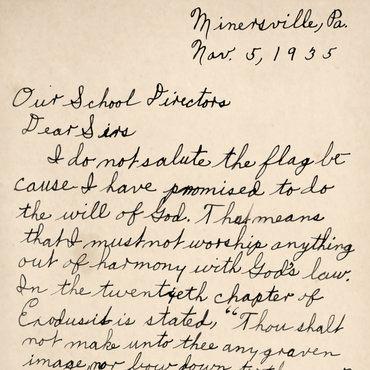

THE CASE

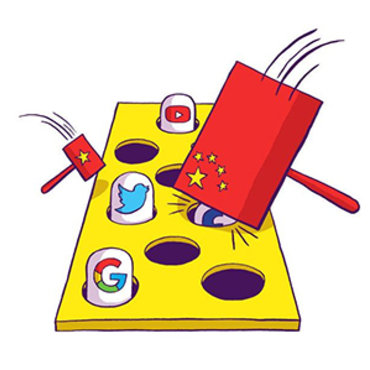

You are the mayor of Skokie, Ill., a community with a large Jewish population, including thousands of Holocaust survivors. Members of a political party with a history of divisive and discriminatory views want to stage a march in your town. In past public gatherings, the members of this party have worn uniforms that resemble the robes worn by the Ku Klux Klan (a hate group that promotes white supremacy) and armbands with swastikas, a symbol of the Nazi Party. The Nazi Party, led by Adolf Hitler, was responsible for the death of millions of Jews and members of other minority groups in the World War II Holocaust.

Although the party has said this march is about protesting new rules limiting political demonstrations in public parks, many members of your community suspect that it will also be used as an opportunity to promote the group’s anti-Semitic and anti-integration views and to intimidate local residents. The marchers argue that because they have given fair warning of when and where the march will take place (in addition to public announcements, they have advertised the planned gathering in the local newspaper) residents who are fearful can avoid the protest.

Community members are rallying together to try to stop this demonstration, which many see as similar to Nazi demonstrations against Jews during World War II because of the views being expressed and the display of swastikas. A local circuit court has ruled that the march cannot take place because of the real and significant potential that it will turn violent. But the party is appealing the ruling, and your community is looking to you for guidance on what to do next.

Should you allow this protest to proceed?

-

No. With the choice of location and plan to display swastikas, this event seems intended to intimidate residents and brings too great a risk of violence.

It is not reasonable to expect anyone who disagrees with this group’s views to simply ignore this very public display, and clashes between the protesters and angry citizens could easily get out of hand.

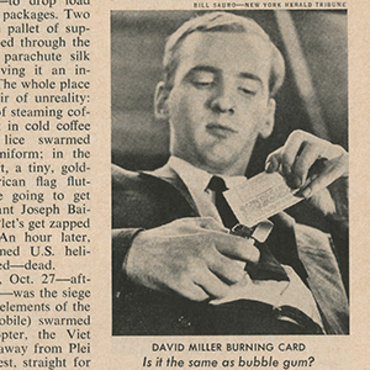

"I also defend the (First) Amendment. But this is like calling 'Fire!' in a crowded theater."

-

?Bettmann/Getty Images

?Bettmann/Getty ImagesYes. Although this group’s views are hateful and go against the beliefs of many of your town’s residents, they still have a constitutional right to gather and protest like any other political group.

Residents who disagree with their message and symbolism can either stay away or peacefully counterprotest.

"By forcing the 'free speech’ … issue in Skokie (Ill.) we are fighting for our basic rights everywhere."

- Should the First Amendment — which protects the freedom of speech, assembly and petition —protect this protest? Why or why not?

- What types of rules or restrictions could be put in place to allow the march to take place but limit the potential for harm or violence? How would you control the activities allowed, location, timing, symbols and messages displayed, etc.?

- Do you think citizens should have a right to prevent fearful imagery or hateful language from being brought into their own communities?

- Whose responsibility is it to prevent violence during a political demonstration? The organizers? Participants? Those who show up to counterprotest? City leaders? Police?

- Is providing a public announcement a reasonable way to make sure that people who disagree with a protest’s topic stay away and avoid conflict? Should people who disagree with the ideas being presented at a demonstration be able to confront the demonstrators?

- In today’s social and political climate, are there any views or symbols that should be deemed too controversial for public protests?