2018: Revisiting a Deadly Rally

Should white supremacists be allowed to gather on the first anniversary of a deadly protest?

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

This Critical Debate is part of a Debate Comparison:

See all Debate Comparisons- Constitution

- Current Events

- Protests

- 7-12

- College/University

Do your students know what they’re free to say online? At school? On a public street corner?

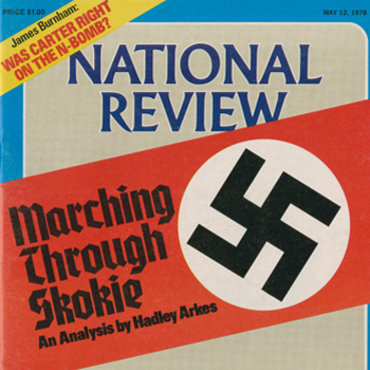

From censorship to cyberbullying, the First Amendment and the freedoms it protects are as hotly contested as ever. This case study is part of our EDCollection that explores 16 free speech debates ranging from the founding of our nation to recent headlines to illustrate what free speech actually means, where it comes from, and how far it can go. It’s information everyone needs to voice their opinions and shape our society.

Using This EDCollection

This EDCollection is designed to meet the needs of a wide range of circumstances and curricula. Whether you’re a social studies teacher looking for a complete unit or an English teacher looking to spend a single class period on free expression, there’s something for everyone. This complete package will lead students to the outcomes below.

Build Fact-Based Arguments

The Free Speech Essentials curriculum aligns with state and national standards as it guides students to take a position, find evidence to support it, and make a compelling presentation to their peers. Potential evidence includes:

- Writings, images and video from 1787 to 2018

- Primary and secondary sources

Connect Past and Present

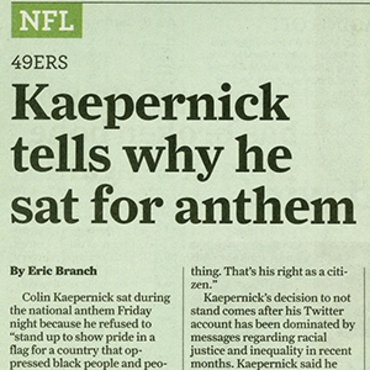

Six of the eight pairs of case studies in this EDCollection juxtapose real historical and contemporary debates on a key free expression question. These pairs allow students to explore the historical origins of a key question — and get context for tackling today’s hot-button issues. The other two pairs provide different perspectives on a contemporary issue. Topics include:

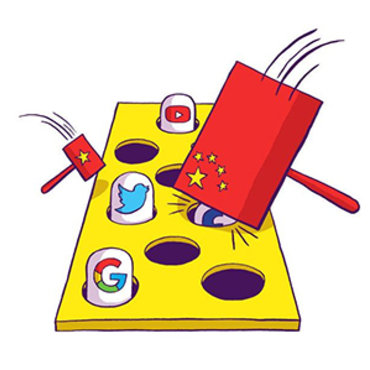

- Federalism and Facebook

- Presidents and the press

- Censorship and cyberbullying

Keep Calm (and Debate On)

Our case studies are structured to help students experience the passion of the real players, while still practicing productive debate. We provide everything you need to prepare and fully support your students as they engage in civil discourse and debates:

- Overviews of the outcomes

- Clear scenarios and suggested positions

- Suggested discussion prompts.

Today’s social and political landscape can sometimes make free speech and First Amendment controversies seem too explosive for classroom exploration. We’ve created Free Speech Essentials to give you the tools you need to start tackling these vital topics with confidence and create enriching experiences for your students.

— The NewseumED Team

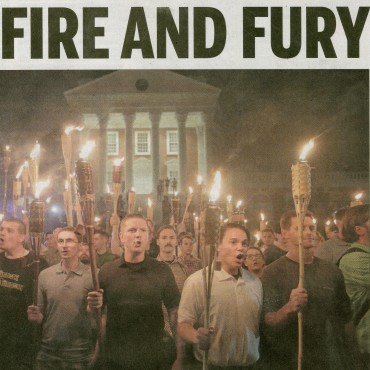

THE CASE

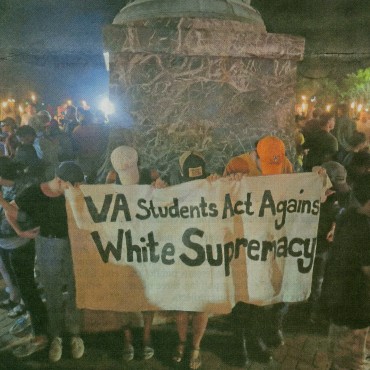

You are the mayor of Charlottesville, Va. Months earlier a far-right activist organized a rally in your city that turned violent. Your city was targeted in part because it had recently renamed a public park that used to honor a Confederate Civil War general. The park is now called Emancipation Park, and the city has also announced plans to remove a statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee from the park. Many of the individuals and groups drawn to the rally were neo-Nazi and white nationalists. White nationalists advocate for the supremacy of white races over other races.

Your city made some efforts to limit the impact of the rally, including a last-minute attempt to relocate it to a larger park to accommodate more people and move it away from the high-traffic downtown area, but a judge ruled that this move violated the protesters’ First Amendment rights to speech and assembly.

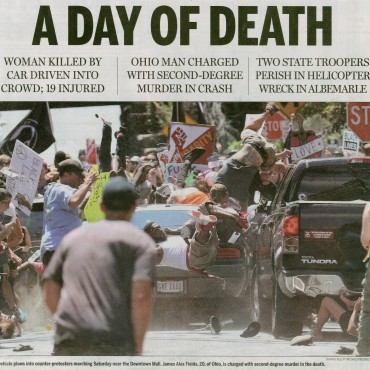

On the day of the rally, as the crowds of protesters and counterprotesters grew, they spilled out of the park and into the downtown streets. Protesters from white nationalist groups, counterprotesters and some bystanders were injured when participants began hitting each other with sticks and spraying chemical irritants. A counterprotester was killed and many more injured when a self-proclaimed white nationalist drove his car into a crowd.

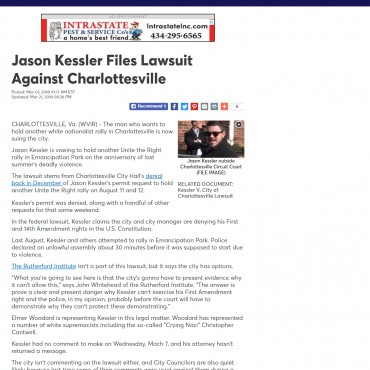

Now the same group wants to return to your city to hold a one-year anniversary rally. Your city manager denied its application for a permit, citing the city’s lack of resources to keep all citizens safe regardless of their views. But the organizer of the rally is now suing your city for the right to hold his Unite the Right rally there, claiming you are discriminating against the content of his speech, which would violate the First Amendment. He argues that violence erupted at the original protest because of poor planning by city officials and because law enforcement failed to keep counterprotesters away from the rally participants.

Should you change course and grant the permit for an anniversary rally?

-

?City of Charlottesville, Office of the City Manager

?City of Charlottesville, Office of the City ManagerNo. The city manager was correct that the city doesn’t have the resources to ensure public safety if this event again draws clashing crowds.

This rally poses a threat to the participants and the residents of your city, and you must put these concerns first.

“The applicant requests that police keep ‘opposing sides’ separate and that police ‘leave’ a ‘clear path into event without threat of violence,’ but city does not have the ability to determine or sort individuals according to what ‘side’ they are on, and no reasonable allocation of city funds or resources can guarantee that event participants will be free of any ‘threat of violence.’”

-

?Jason Andrew/Getty Images

?Jason Andrew/Getty ImagesYes. The city cannot discriminate against this organizer’s viewpoint because of the past actions of a few violent individuals.

Your main objections to this event are rooted in the content of this speech, and the First Amendment does not allow you to block an event on that basis. You must make an effort to accommodate this request.

“[I]t is virtually impossible to articulate a standard for suppression of speech that would not afford government officials dangerously broad discretion and invite discrimination against particular viewpoints.”

- Is it possible to balance the First Amendment freedoms of rally organizers and participants with the need for public safety? If so, how? If not, why not?

- Should the First Amendment protect public gatherings that are likely to become violent? How would you measure the likelihood of violence?

- Should groups involved in violent protests be allowed to gather in public again? In the same place? For the same type of event?

- How should you decide who is to blame for violence at rallies where two sides clash?

- Is it possible for law enforcement to keep the different “sides” at a rally separate from each other?

- Are some ideas or opinions simply too controversial to be the basis for public protests?

- What could police and city officials do to minimize the risk of violence at this type of event while also allowing all sides to voice their opinions?

- Does the timing of this rally – planned for the anniversary of the first event – matter? Would choosing a different date for the gathering affect your position?