Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

Sign Up

?

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

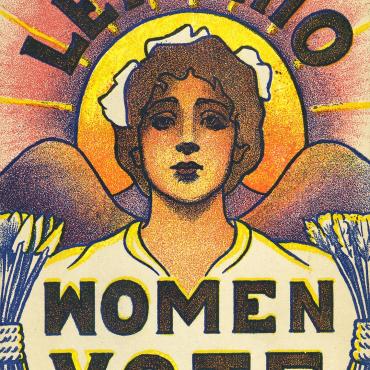

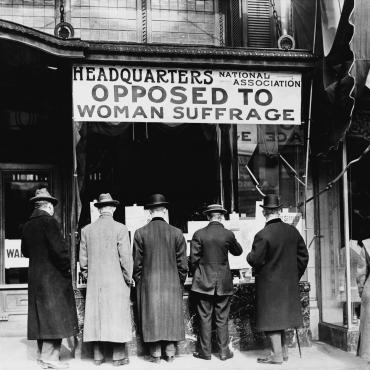

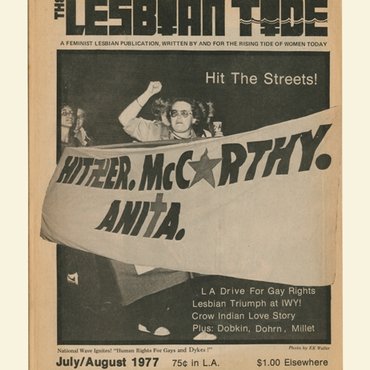

Topic(s)

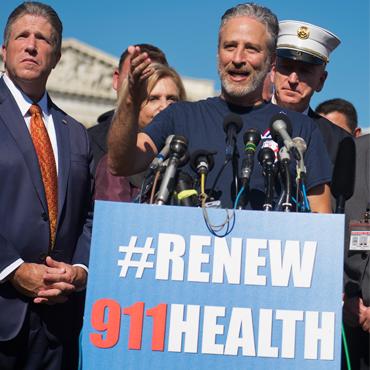

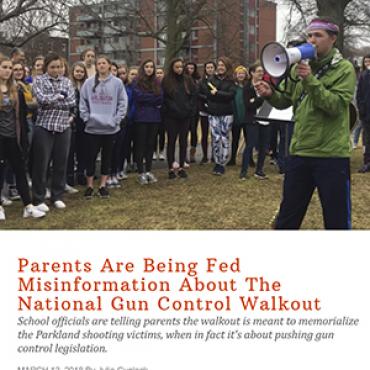

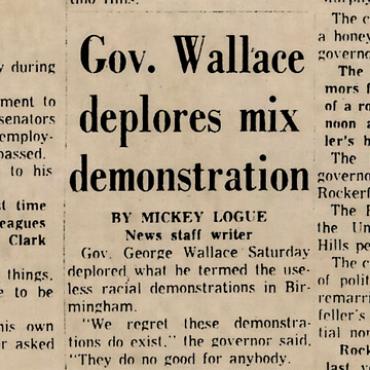

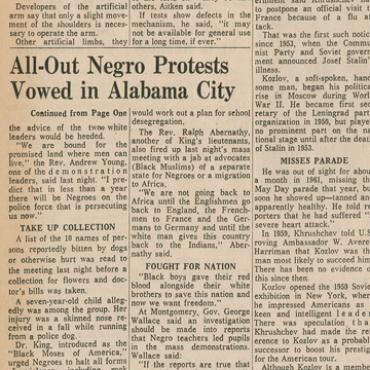

- Politics

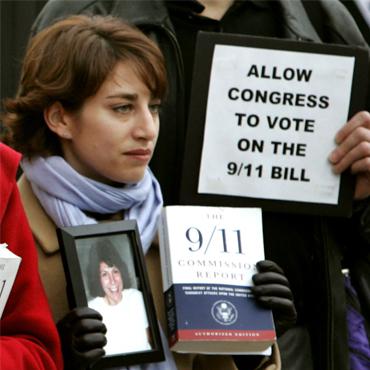

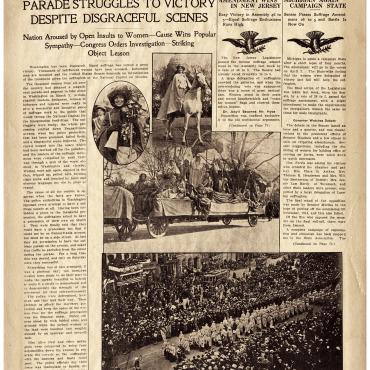

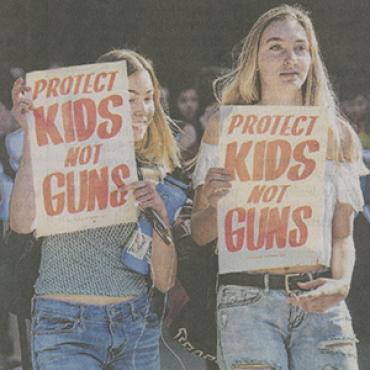

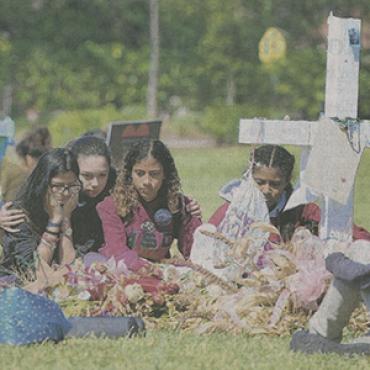

- Protests

- Women's Rights