Photographic Lies in Stalin's Russia: Online Exhibit

Armed with airbrushes and scalpels, censors routinely tried to erase enemies of Stalin from Soviet history by falsifying photographs.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Journalism

- Politics

- World History

Photographs can lie. They certainly did in the Soviet Union from 1929 to 1953, the years of Joseph Stalin's dictatorial rule. Stalin's agents routinely arrested and killed as "enemies of the people" anyone who disagreed with his politics. Communist Party workers then tried to remove any trace of these people from the state's photographic archives, and so from the media.

By the 1930s, communist "truth" circulated worldwide in party approved books. With airbrush or ink spot or scalpel, the photo censors worked quietly. But despite their power, they ultimately failed. This exhibit provides a stark visual tour through a society where freedom was not an option — the culture of control that went on to create the Berlin Wall.

Much of the content below appeared in a print exhibit at the Newseum in 1999 and a companion digital exhibit called “The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin's Russia,” based on a 1997 book by David King by the same name. All photographs are licensed by the David King Collection, London.

Obliterated

Joseph Stalin’s bloody reign in the early half of the 20th century was not without certain irony. In the first photo below, the short man strolling with Stalin on the banks of the Moscow-Volga Canal in April 1937 is Nikolai Yezhov. Yezhov was the head of the secret police during Stalin’s “Great Purge” who presided over mass arrests and executions. In 1940, Yezhov was executed himself for disloyalty. It seems only fitting that when Yezhov was airbrushed out of the photograph, he was replaced by the waters of the canal; Yezhov also was commissar of water transport.

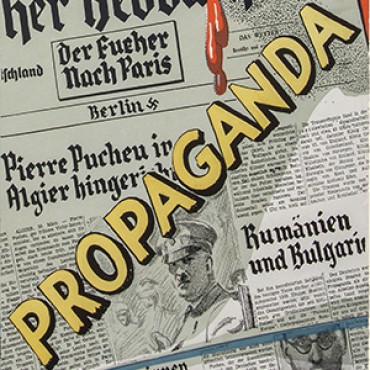

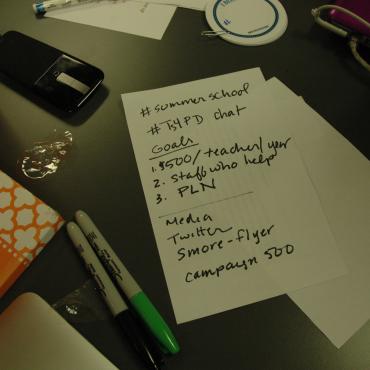

Communism and Propaganda

In the Soviet Union, distorted images were used to further the cause of communism and to boost the reputations of those in power. If photographs are usually considered factual, what happens to the truth when the facts are altered?

Propagandists seized every opportunity to get their message across. In the original photograph on a souvenir postcard, below left, troops pose in Petrograd's Liteiny Prospekt during the first days of the February Revolution in 1917. The sign on the jeweler's building in the background reads, "Watches, gold and silver," and the words on the soldier's flag are hard to make out. In the altered postcard, also released that year, the building sign now reads, "Struggle for your rights," and the flag says "Down with the monarchy — long live the Republic!"

The News in Russia

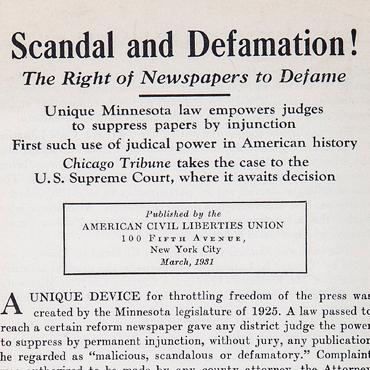

Pravda started as an underground revolutionary Bolshevik newspaper. After the revolution, it became the official newspaper (with Izvestia) for the Communist Party. Its name stands for the word "truth." Propaganda can be even worse than censorship. Under a state-controlled press system, the government can order newspaper editors to print stories the editors know are not true. Early on, Russian revolutionary leaders realized they could force newspapers to print only the concepts, slogans and ideas of Bolshevism.

Leon Trotsky, below left, reads Pravda, the Bolshevik newspaper he founded. In 1925, Stalin ousted Trotsky as commissar of war. Next photo, a citizen has scratched Trotsky's picture from his own history book, as part of the Soviet doctrine of "personal responsibility" to support the Communist Party.

Reinventing the Bolsheviks

Without fanfare, official Soviet photographs were purged of the image of anyone who had fallen from official favor, especially those murdered for political reasons.

Below, Trotsky and Vladimir Ilich Lenin stand at the top of the stairs at a celebration in Red Square on the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution in 1919. The two were leaders of the Russian Revolution, which placed the Bolsheviks in power. To make the photo suitable for a 1967 book of Lenin photographs, Trotsky — who was stripped of power and exiled under Lenin's successor, Stalin — was removed. Also airbrushed out: Lev Kamenev, in leather cap and glasses to Lenin's left in original photo, who was executed in Stalin's Great Purge.

Reinventing the Bolsheviks II

This is one of the earliest and most famous examples of Stalinist retouching. Trotsky not only became a pest to budding Soviet communism, but he was a pesky presence in many photographs of significance to Lenin's history, like this one taken in front of Moscow's Bolshoi Theater in 1920. In the first photograph, you see Trotsky (in uniform beside the wooden pulpit) with Lenin as he rallies the troops to fight Poland. This photograph came to be a symbol of revolutionary Russia, but after Trotsky's downfall, Trotsky had to go. His image was removed from all widely distributed reproductions.

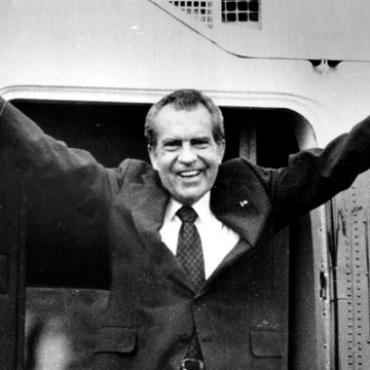

Stalin Controls His Imagery

Stalin saw himself as the "great leader and teacher of the Soviet people." He wanted the media to picture him as the true friend, comrade and successor of Lenin. Yet during Stalin's Great Purge of enemies, untold millions succumbed to famine or execution. Stalin needed photographs to be altered to hide any evidence that didn't fit his message.

The "official image" below is one example of happy images covering up sorrow, scheming and horror. This 1936 photograph on the front page of Izvestia of Stalin with 6-year-old Gelya Markizova became a famous Soviet icon titled "Friend of the Little Children." Yet Gelya's father, Ardan, was shot the next year for allegedly plotting against Stalin and her mother, Dominica, died under mysterious circumstances.

The image in the newspaper is a reproduction. In the original photo, M.I. Erbanov, party secretary of the Buryat Mongol Socialist Republic, appeared smiling to the right of the girl. He was later purged from the party.

Existence Denied

Many people — not just party officials — felt the sting of the airbrush. In a display of Stalin's contempt for ordinary workers, an attendant who helpfully pointed the way for "The Boss" at the Sixteenth Party Congress in 1930 was dutifully removed in a version printed soon afterward in Projektor magazine. Stalin, it seemed, didn't need any help.

The Soviet Message

Beginning in 1928, Latvian artist Gustav Klutsis employed militant typography and montage (combining images) to promote Soviet messages through eye-popping posters. His main mission was to glorify Stalin, which he did by making the dictator's image large and always clearly in command. And when Stalin's purges claimed the reputations and the lives of the once-loyal, Klutsis reworked his material, as he did with this photomontage, beginning by hacking two army marshals from Stalin's side. Marshal Yegorov, who remains on the right in the photomontage, was tortured to death in 1939. Klutsis also suffered under Stalin's regime; he was arrested in 1938 and eventually killed.

Death Is Not the End

Even in ultimate repose, Stalin reaps the benefit of photo manipulation in this Russian newspaper, Pravda Ukrainy. A simple photo of the man lying in state was not enough. So after Stalin's death, in early March 1953, a photomontage was manufactured for use in the Soviet press. Its mission was not only to perpetuate Stalin's crudely magnified larger-than-life image, but also to show great apprehension on the faces of Politburo members, whose images were plucked from previous photos and pasted in to this mourning scene.