The Marines and Tet: The Battle That Changed the Vietnam War

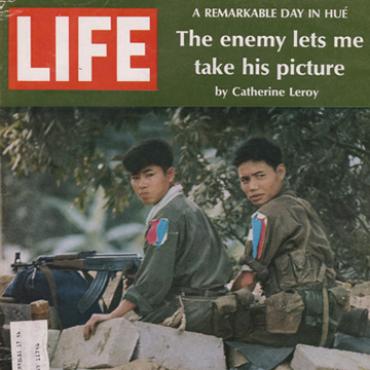

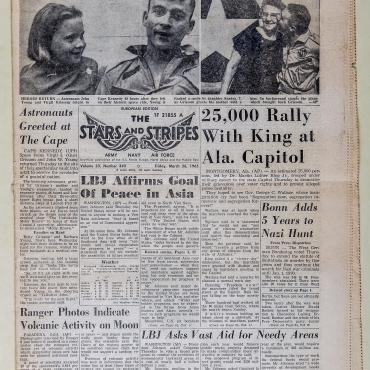

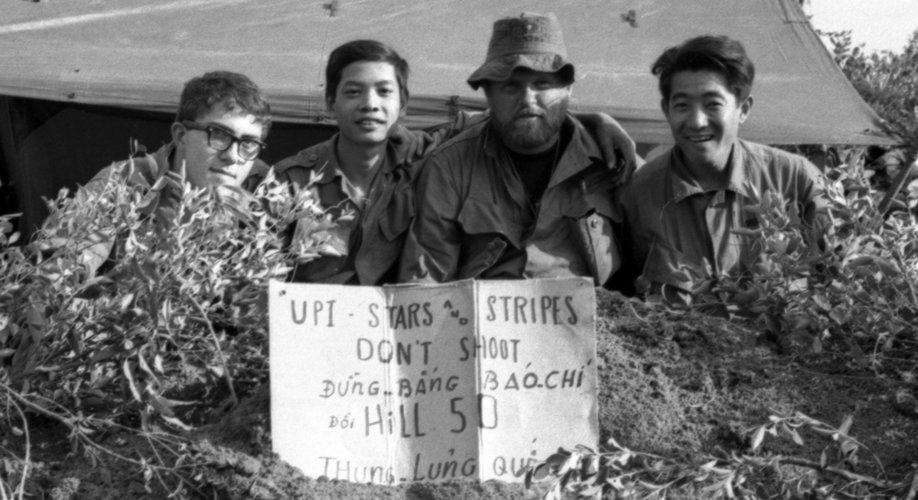

Opened as an exhibit in the Newseum to mark the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive, this collection of photographs showcases the work of Stars and Stripes photographer John Olson, who spent three days with U.S. Marines during the Battle of Hue in 1968.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Cold War

- Journalism

- Vietnam War

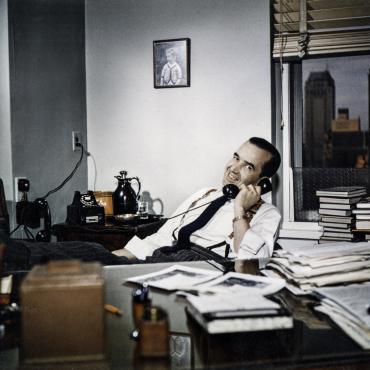

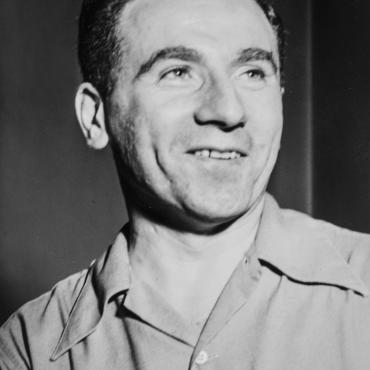

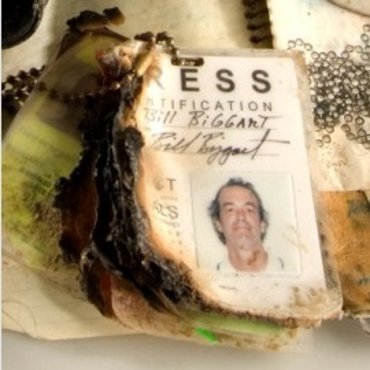

Drafted into the Army at age 19, John Olson, at left, was a photographer for the military publication Stars and Stripes in Vietnam. During the Tet Offensive, Olson followed the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines Regiment through the city of Hue with four cameras slung around his neck — one camera to shoot black and white film and three for color. Olson's photographs from the battle appeared in a six-page spread in Life magazine's March 1968 issue. He won the prestigious Robert Capa Gold Medal Award for his war photography.

Chapter 1: Combat in the Courtyard

"Combat in a built-up area is close, personal and extremely violent."

— Maj. Bob Thompson, commander of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, including Delta Company

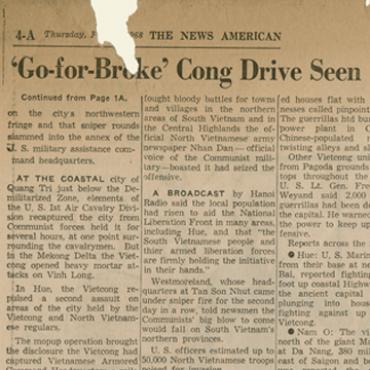

On Jan. 31, 1968, communist forces had taken control of Hue, the third largest city in South Vietnam. U.S. forces began their counterassault at daybreak on Feb. 15 as the Delta Company moved quietly through the maze-like alleyways and courtyards of the ancient Citadel. The oldest part of Hue, this fortification was built to protect the city when it served as the imperial capital of Vietnam.

Troops familiar with fighting in dense jungles were disoriented by the combat in tightly packed streets. Sounds ricocheted off walls adding to the confusion of urban combat. Crumbled buildings and blind corners made perfect sniper nests and ambush points. It was chaos.

Listen to Thompson describe the difficulties of fighting within the Citadel.

Combat in the Courtyard

The Lookout

Holding a bandage to a neck wound, a Marine stood guard at the window, his rifle at the ready. As North Vietnamese soldiers surrounded the villa, another wounded Marine recited the Lord's Prayer.

A Brutal Attack

Blood splattered on the courtyard marked the remains of a Marine radio operator who was killed by enemy rockets. His fellow Marines scrambled to take cover in neighboring villas, answering the enemy with a barrage of bullets.

Seeking Cover

A Marine who was shot through both legs dragged his body through the rubble in the courtyard, desperately seeking cover. Another Marine offered the end of his rifle as a lifeline, pulling the wounded Marine to relative safety inside a villa.

Tending the Wounded

Inside a villa, Marines used anything at hand to treat the injured. They covered a Marine who had been shot in the chest in curtains and mosquito netting to keep him warm.

Evacuating the Injured

Low on ammunition after a 90-minute battle, the Marines got much-needed reinforcements with the arrival of Bravo Company. The Marines used doors they had ripped off the hinges as stretchers to evacuate the injured.

Taking Aim

Marines prepared to fire a mortar in the streets of the Citadel in Hue.

Injured Child

A Marine cradled an injured child as he walked through the streets of Hue during the Tet Offensive.

Chapter 2: The Assault on Dong Ba Tower

"It was just absolutely utter devastation, burned out trucks and bodies on the road. The stench of death was there all the time."

— Capt. Myron Harrington, Delta Company commander

By mid-afternoon of Feb. 15, Capt. Myron Harrington — commander of Delta Company — and his men regrouped at Dong Ba Tower. One of the city's highest points, the tower was the main military objective for U.S. forces as it would give them a strategic vantage point within the city. The strategy was straightforward: Charge the tower, kill the remaining enemy soldiers and hold it. The reality would be far less easy. North Vietnamese army soldiers crouched in sniper foxholes within the tower and hid behind rubble to shoot U.S. Marines.

Later that day, Harrington's men launched their assault. Rocket and mortar fire cratered the ground, bullets found their targets and six Marines were killed. By nightfall, the U.S. Marines were in control of the tower.

Listen to Harrington reflect on the initial assault he commanded to take the Dong Ba Tower.

The Assault on Dong Ba Tower

Scouting the Battlefield

Capt. Myron Harrington, left, radio operator Cpl. Steve Wilson, center, and Harrington's unidentified bodyguard crouched to avoid enemy fire. U.S. Marines outnumbered the North Vietnamese soldiers holding the tower. But the high ground gave the position a strategic advantage and made it easier for the enemy to fire on the Marines.

On Alert

A Marine aimed a rifle with a high-powered scope while a second Marine used binoculars to scan for the source of enemy fire near Dong Ba Tower.

A Break in the Fighting

A group of U.S. Marines took a break from the combat under a makeshift shelter and lit a fire.

Chapter 3: Holding the Position

"It was a suicide mission."

— Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms, Delta Company

Even after taking the Dong Ba Tower on the evening of Feb. 15, it would not be a peaceful night for the seven Marines in charge of holding the position. The enemy forces were able to regroup shortly after their defeat and launch a second attack on the tower before dawn on Feb. 16. The occupying Marines were blasted off their position during the conflict as the tower was retaken by the communist forces. U.S. forces would now need to fight to regain control of the tower for the second time in two days.

Listen to Thoms describe the evening his command spent attempting to hold their position on the Dong Ba Tower.

Holding the Position

The Cajun Points

Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms pointed toward Dong Ba Tower, directing machine gunners to fire and protect the Marines attempting to capture the tower. Thoms, nicknamed "Cajun Bob," and his unit were repeatedly knocked back by enemy fire. The explosions burned his shirt and helmet covering and split his pants from ankle to crotch. The shirts he wears in this photo were taken from a dead North Vietnamese soldier.

Chapter 4: The Final Assault

"I looked up and I did see a cross on his uniform, and I knew he was a chaplain. I didn't know how much time I had."

— Lance Cpl. Richard Prince, Delta Company

At 9:30 a.m. Feb. 16, twelve U.S. Marines launched their final assault on the Dong Ba Tower, nicknamed "the hill" because it looked like a pile of rubble after the initial combat. They fought the communist forces throughout the morning and by midday they had reclaimed the tower. By the end of the fight to take Dong Ba Tower, six Marines were dead and 50 others injured. Marines pulled 24 enemy bodies from the rubble after they consolidated their positions on the tower.

Listen to Cpl. Selwyn "S-Man" Taitt talk about the carnage he witnessed as he participated in the final assault on the Dong Ba Tower.

Listen to Prince reflect on being shot in the neck by a sniper after helping complete the final assault on the Dong Ba Tower.

The Final Assault

Storming the Tower

On the morning of Feb. 16, U.S. Marines began their second, and final, attack on the tower. Five hours earlier, the squad had been blasted off the tower.

A Heavy Toll

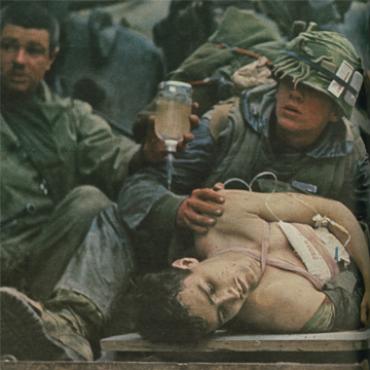

Lance Cpl. Richard Prince, the Marine on the right, helped an unidentified U.S. Navy hospital corpsman administer first aid to a wounded Marine. The next day, Prince was shot in the neck by sniper fire. He recovered from his wound on the Navy hospital ship, the USS Repose.

Chapter 5: A Final Blessing

"He told us, he said, 'I don't know if you guys, some of you will make it to Sunday' and then he came out to where we were and said, 'I'd like to give you guys last rites.'"

— Lance Cpl. Richard Hill

U.S. forces had greatly underestimated the enemy's numbers and resolve. Told by his commanders the mission was a "mop-up" that would take just a few days, Maj. Bob Thompson was chilled to see streets lined with dead bodies and burned-out vehicles as his troops made their way to the U.S. command post in Hue.

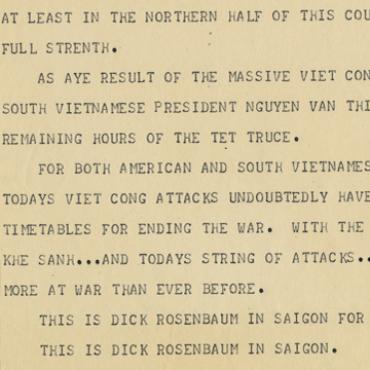

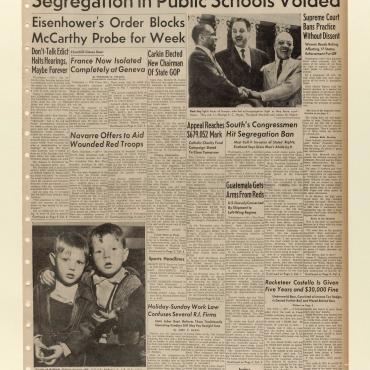

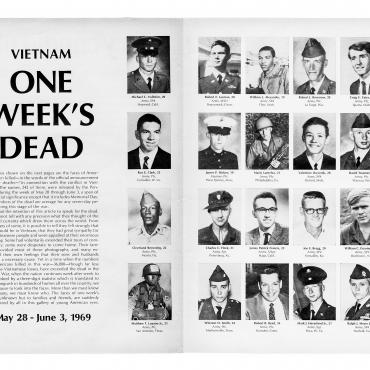

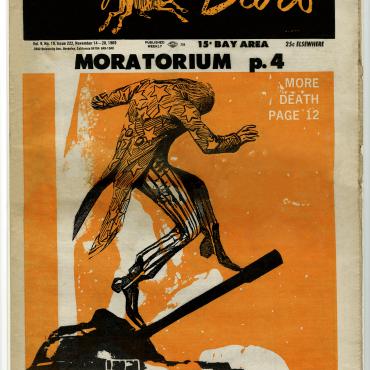

Tet was a turning point in the American public's support of the war. The U.S. government had justified the war as essential to halting the spread of communism in Asia. But by 1968, as American casualties continued to mount, public opinion against the war grew stronger.

Listen to Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms describe Catholic chaplain, Maj. Aloysius S. McGonigal, and his "wild man" pursuit to administer last rites to fallen Marines.

Listen to Lance Cpl. Richard Hill reflect on the anguish felt from receiving last rites before going off to battle.

A Final Blessing

Administering Last Rites

Maj. Aloysius S. McGonigal, a Catholic chaplain, administered last rites to a dying Marine. McGonigal crossed the Perfume River in Hue to attach himself to the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines Regiment the day before they began their mission to take the Dong Ba Tower. Soon after this photo was taken, McGonigal was killed.

Chapter 6: Fire in the Hole

"All I could hear people say, 'I'm hit, I'm hit, I'm hit.' And I kept thinking, when is a bullet going to hit me?"

— Cpl. Selwyn Taitt, Delta Company

During the Marines final assault on the tower, Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms was attempting to draw the enemy forces out of their positions. Thoms had tasked fellow Marine Cpl. Selwyn Taitt, nicknamed "S-Man," to "grab every grenade he could get a hold of," referring to fragmentation grenades. However, "S-Man" went out and collected every grenade he could find, including red-smoke and tear-gas grenades. The various types of explosions caused the North Vietnamese forces to become disoriented and scatter. The ensuing chaos allowed the Marines to continue their assault up the tower.

Listen to Thoms describe how Cpl. Selwyn "S-Man" Taitt's misinterpretation of his instructions enabled them to blast their way up the Dong Ba Tower.

Fire in the Hole

Taking Cover

After taking enemy fire and treating the wounded, Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms, upper left, Cpl. Selwyn "S-Man" Taitt, top right, and the remaining members of the assault took cover among the rubble.

Chapter 7: A Marine's Dying Wish

"If there's anything close to hell, it had to be Hue."

— Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms, Delta Company

Pfc.Jim Walsh was shot through both legs during the assault on the Dong Ba Tower, but managed to survive his injuries. Decades later, he tracked down his platoon commander at Hue, Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms. "You led me through that and I made it," said Walsh, who revealed he was dying of cancer. "I want to go to heaven. I want you to lead me through this." Thoms enlisted the remaining members of the Delta Company to support Walsh in his final days as he was estranged from his family. Thoms sent Walsh a Bible and called regularly to discuss the verses. Walsh died three months after reconnecting with Thoms. Because he did not have a will, the remaining members of the Delta Company arranged for his funeral. Walsh's hospice worker thanked Thoms and the Delta Company as she was the only person who was present for his three-volley salute.

Listen to Thoms discuss the remaining members of the Delta Company's contact with Walsh during his dying days.

A Marine's Dying Wish

Shot on the Tower

Near the top of the tower, Olson photographed a corpsman, right, treating Pfc. Jim Walsh, lying across the crumbled bricks with his eyes closed. Moments before, Walsh was shot through both legs.

Chapter 8: 'We're Marines, Let's Go!'

"I'm thinking about what we need to do, the seven of us, to survive on top of this tower."

— Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms, Delta Company

One of the seven men assigned to hold the tower the night of Feb. 15, an unidentified Marine nicknamed "Lurch" thought he was shot between the eyes. Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms soon realized his fellow Marine had been hit by a rock, not a bullet. "So we had some tape and he taped his glasses back together and he was so happy that he wasn't shot between the eyes," Thoms said. "We celebrated by lighting another cigarette. Even guys who didn't smoke would take a drag on this Salem cigarette and we'd wait for the next probe. And this went on all night." After eventually being blown off of the tower, "Lurch" urged his fellow Marines to battle the next day with the battle cry: "We're Marines, let's go!"

Listen to Thoms reflect on the first night he and his fellow Marines were tasked with holding the Dong Ba Tower.

'We're Marines, Let's Go!'

Ace of Spades

Here, "Lurch" is pictured taking a break after Dong Ba Tower was secured for good with an ace of spades playing card tucked in his helmet. This specific playing card was meant to symbolize death and ill-fortune to the communist forces. As a means of psychological warfare, ace of spade playing cards were often left on dead enemy bodies or dropped from the sky to litter the battlefields.

Chapter 9: Casualties of Hue

"I went into the Hue City battle with approximately 120 Marines. At the end of the battle there were 39 of us that were still standing."

— Capt. Myron Harrington, Delta Company commander

Although the Battle of Hue was a military success for U.S. forces, the casualties suffered and psychological effects felt from the combat far outweighed their victory on the battlefield. Even after the Dong Ba Tower was secured on Feb. 17, fighting would continue in Hue until late February when the U.S. Marines seized full control of the city. All told, 216 U.S. troops, more than 400 South Vietnamese troops and 2,500 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers were killed over the course of the month of fighting. Counting civilian losses, more than 7,000 died, making it one of the deadliest battles of the Vietnam War.

Listen to Lance Cpl. Richard Hill share his experience from his ride on the tank after receiving shrapnel in both legs.

Listen to Capt. Mayer Katz discuss his time serving as one of only six surgeons at the Phu Bai Combat Base, which housed the closest U.S. medical facility to Hue.

Casualties of Hue

The Tank

On Feb. 17, two weeks into the Tet Offensive, photographer John Olson captured his photograph of injured Marines being medically evacuated on top of a Patton tank. It became one of the defining images of the Vietnam War, published in the March 8, 1968, issue of Life magazine. The debate over the identity of the Marine lying on his side with his chest exposed continues to the present day. Olson identified the Marine as Pfc. A.B. Grantham, who was severely injured during the fighting and also claims to be the injured Marine in the photo. However, as recently as February of 2019, The New York Times wrote an article on the photo and identified the Marine as Pfc. James Blaine who was shot Feb. 15, 1968, and died that day.

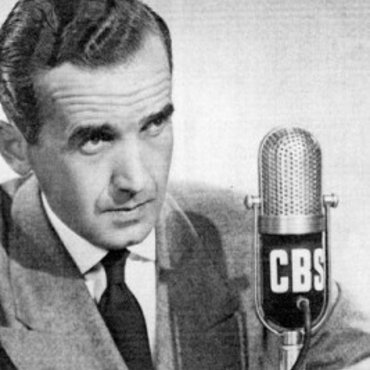

Chapter 10: The Cost of Tet

"It seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate."

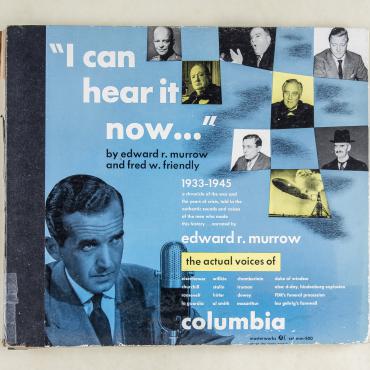

— CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite after his 1968 trip to Vietnam

By the end of the Tet Offensive in September of 1968, both sides had suffered heavy losses. About 2,500 American troops and 40,000 communist soldiers had been killed with even more sustaining injuries during the fighting.

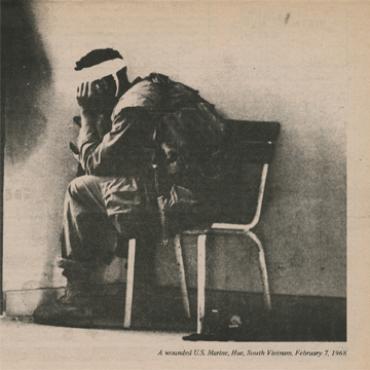

The physical and mental scars from the Tet Offensive — particularly the deadly Battle of Hue — stayed with the returning Marines long after the Vietnam War ended. The stigma of participating in an unpopular war mixed with the horrors of bloody urban combat haunted Marines who were unable or unwilling to talk about their experiences. One look at a photograph or film clip from Hue would ignite the memory of chilly rainy days, the smell of death and the fear and anger of war.

Listen to Lance Cpl. Leon Dyes talk about his struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder after he returned from Vietnam.

Listen to Lance Cpl. Richard Schlagel describe his experiences at Hue and how they changed his psyche upon returning home.